There are other sections of this Ancestry providing background about the Nannariello’s and Martiniello’s and Passarella’s and many other families. Attempts are made to document who these families and people are, how did they get to the United States, and what happened when their chosen country became their homes. However, their stories happened in a time and place.

This section provides some limited context by describing Calitri and Italy at various times and puts these good people into that arena. Their lives happened in a time and place and hopefully will inform us and provide insights into their lives.

In 1921, when Canio Nannariello immigrated to the United States, he was joined by more than two and a half million other Italians who immigrated. Most of those immigrants were from the Mezzogiorno or the Southern part of Italy. We have not done the research to determine how many millions departed from various countries in Europe and other continents in that same year. The next year, the United States Congress established a quota system for all or most countries, and the immigration significantly slowed down.

For this particular Ancestry, some context is provided by focusing on topics about Italy and the Mezzogiorno and Calitri and other topics. Calitri, most certainly, was not Westchester County, New York. And Westchester Country, New York was not Calitri. Possibly, the context provided in this section will assist in some small way to answering the question: “Why did you leave Calitri and go to the United States.” Possibly it will not, but it can be wonderful speculation and worth thinking about. All Readers would relish the opportunity to have oral history that documented the response to that question from everyone mentioned in this Ancestry that immigrated. Too many of us failed to ask, and too many of those who immigrated failed to offer.

Our lives and history, whether Italy or the United States or any of the more than two hundred countries in the world, do not happen in a vacuum. There is a context of place and time and events that provides a platform to understand history and posit why things happened. That is the historian’s job. We are not historians, but provide some historical insights to understand these people we are writing about, by providing a modest description of the world in which they lived.

Calitri Description

Following is information about Calitri taken from the History of Calitri book by Vito Acocella. The story of this book and how it came to be written are covered in detail in another section. Also, the entire History of Calitri book of twenty seven chapters is indexed and available for searching by chapter. This information is provided because the story of the Nannariello family, many of whom immigrated to the United States, started in this lovely village on top of a mountain in the Region of Compania (comparable to US states) and in the Province of Avellino (comparable to US counties). Also, Calitri is a Commune. A commune is an Italian political organization for some towns providing certain local powers and relationships with the Province and Region.

Following is an excerpt quote from the History of Calitri.

Calitri is in Campania near the borders of the regions of Apulia and Basilicata. It is approximately 530 meters or about 1,740 ft above sea level, so on even on the hottest day there is generally a breeze. The Antico Borgo is in the oldest section of the town, the Centro Storico, at the top of which are the remains of a castle which predates the 12th century. The Borgo itself is a labyrinth of historic houses which have, over the centuries, been built into the hillside. Stone and marble stairs frequently under old stone arches, connect the streets. Calitri suffered a devastating earthquake in 1980 and has only been partially rebuilt. The Castello at the top of its distinctive cone shaped hilltop is very impressive for its strong architectural forms. In recent reconstructions they are remerging as an important and physically attractive feature of the town. Other recent excavation and reconstruction of an ancient Neviera in the Gagliano section of the town above the cemetery reveals an extensive underground, domed, ice-house of about 15 meters (50 ft) in height and 7.6 meters (25 ft) in horizontal circumference. Restored by the family of Giovanni Cerreta, the Neviera can be visited by inquiring at the Town’s tourist office in the Centro Storico.

Italian History and Independence

Luigi and Francesca Martiniello Nannariello were born in the 1860’s and in the midst of significant political and social and historical and government change. The changes occurring in Italy at the time of their birth would redefine what it meant to be Italian and eventually the definition of Italy as a united republic. The Nannariello ancestry goes back four centuries and more before their birth. There are records of the Nannariello family in the 1500’s. The history and ancestry of a country or a particular family does not happen in a vacuum, but happens in an historical time and for a duration and in various locations.

Italy was not a united country before the 1860’s. The enigma of this beautifully shaped country into a symbolic “boot,” possibly provides one of the most identifiable geographical footprints of any country in the world. Italy was a peninsula of city-states and different and competing interests of several foreign governments and many internal governances.

The peninsula of Italy had millenniums of history, including over one thousand years of rule by the Romans. The Romans have made an indelible and historic impact on modern day Italy including but not limited to language, art, cuisine, architecture, economics, social context, culture, politics, and more.

However, all of the history and tradition across the millenniums prior to the 1860’s, positioned what is now modern day Italy to enter the Nineteenth Century not as an organized country with a unified form of government, but as a series of cities and city-states and holdings of other countries. One could go back to Italy in the early 1800’s and be challenged to know what it meant to “be Italian.”

A citation is provided to Wikipedia, the ubiquitous Internet encyclopedia, for providing the history of the circumstances that resulted in Italy becoming a republic. The narrative provides a uniform insight of what it means to be Italian and how that definition was arrived at. The Wikipedia history covers the time from the early 1840’s to the end of the Second World War.

Following is the enlightening and ambitious Wikipedia narrative.

Revolutions of 1848–1849 and First Italian War of Independence

Main articles: Revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states and First Italian War of Independence

Execution of the Bandiera Brothers

In 1844, two brothers from Venice, Attilio and Emilio Bandiera, members of the Giovine Italia, planned to make a raid on the Calabrian coast against the Kingdom of Two Sicilies in support of Italian unification. They assembled a band of about twenty men ready to sacrifice their lives, and set sail on their venture on 12 June 1844. Four days later they landed near Crotone, intending to go to Cosenza, liberate the political prisoners, and issue their proclamations. Tragically for the Bandiera brothers, they did not find the insurgent band they were told awaited them, so they moved towards La Sila. They were ultimately betrayed by one of their party, the Corsican Pietro Boccheciampe, and by some peasants who believed them to be Turkish pirates. A detachment of gendarmes and volunteers were sent against them, and after a short fight the whole band was taken prisoner and escorted to Cosenza, where a number of Calabrians who had taken part in a previous rising were also under arrest. The Bandiera brothers and their nine companions were executed by firing squad; some accounts state they cried “Viva l’Italia!” (“Long live Italy!”) as they fell. The moral effect was enormous throughout Italy, the action of the authorities was universally condemned, and the martyrdom of the Bandiera brothers bore fruit in the subsequent revolutions.

In this context, in 1847, the first public performance of the song Il Canto degli Italiani, the Italian national anthem since 1946, took place. Il Canto degli Italiani, written by Goffredo Mameli set to music by Michele Novaro, is also known as the Inno di Mameli, after the author of the lyrics, or Fratelli d’Italia, from its opening line.

On 5 January 1848, the revolutionary disturbances began with a civil disobedience strike in Lombardy, as citizens stopped smoking cigars and playing the lottery, which denied Austria the associated tax revenue.

Shortly after this, revolts began on the island of Sicily and in Naples. In Sicily the revolt resulted in the proclamation of the Kingdom of Sicily with Ruggero Settimo as Chairman of the independent state until 1849, when the Bourbon army took back full control of the island on 15 May 1849 by force.

In February 1848, there were revolts in Tuscany that were relatively nonviolent, after which Grand Duke Leopold II granted the Tuscans a constitution. A breakaway republican provisional government formed in Tuscany during February shortly after this concession. On 21 February, Pope Pius IX granted a constitution to the Papal States, which was both unexpected and surprising considering the historical recalcitrance of the Papacy. On 23 February 1848, King Louis Philippe of France was forced to flee Paris, and a republic was proclaimed. By the time the revolution in Paris occurred, three states of Italy had constitutions—four if one considers Sicily to be a separate state.

Meanwhile, in Lombardy, tensions increased until the Milanese and Venetians rose in revolt on 18 March 1848. The insurrection in Milan succeeded in expelling the Austrian garrison after five days of street fights – 18–22 March (Cinque giornate di Milano). An Austrian army under Marshal Josef Radetzky besieged Milan, but due to defection of many of his troops and the support of the Milanese for the revolt, they were forced to retreat.

Soon, Charles Albert, the King of Sardinia (who ruled Piedmont and Savoy), urged by the Venetians and Milanese to aid their cause, decided this was the moment to unify Italy and declared war on Austria (First Italian Independence War). After initial successes at Goito and Peschiera, he was decisively defeated by Radetzky at the Battle of Custoza on 24 July. An armistice was agreed to, and Radetzky regained control of all of Lombardy-Venetia save Venice itself, where the Republic of San Marco was proclaimed under Daniele Manin.

While Radetzky consolidated control of Lombardy-Venetia and Charles Albert licked his wounds, matters took a more serious turn in other parts of Italy. The monarchs who had reluctantly agreed to constitutions in March came into conflict with their constitutional ministers. At first, the republics had the upper hand, forcing the monarchs to flee their capitals, including Pope Pius IX.

Initially, Pius IX had been something of a reformer, but conflicts with the revolutionaries soured him on the idea of constitutional government. In November 1848, following the assassination of his Minister Pellegrino Rossi, Pius IX fled just before Giuseppe Garibaldi and other patriots arrived in Rome. In early 1849, elections were held for a Constituent Assembly, which proclaimed a Roman Republic on 9 February. On 2 February 1849, at a political rally held in the Apollo Theater, a young Roman priest, the Abbé Carlo Arduini, had made a speech in which he had declared that the temporal power of the popes was a “historical lie, a political imposture, and a religious immorality”.[42] In early March 1849, Giuseppe Mazzini arrived in Rome and was appointed Chief Minister. In the Constitution of the Roman Republic,[43] religious freedom was guaranteed by article 7, the independence of the pope as head of the Catholic Church was guaranteed by article 8 of the Principi fondamentali, while the death penalty was abolished by article 5, and free public education was provided by article 8 of the Titolo I.

Before the powers could respond to the founding of the Roman Republic, Charles Albert, whose army had been trained by the exiled Polish general Albert Chrzanowski, renewed the war with Austria. He was quickly defeated by Radetzky at Novara on 23 March 1849. Charles Albert abdicated in favour of his son, Victor Emmanuel II, and Piedmontese ambitions to unite Italy or conquer Lombardy were, for the moment, brought to an end. The war ended with a treaty signed on 9 August. A popular revolt broke out in Brescia on the same day as the defeat at Novara, but was suppressed by the Austrians ten days later.

There remained the Roman and Venetian Republics. In April, a French force under Charles Oudinot was sent to Rome. Apparently, the French first wished to mediate between the Pope and his subjects, but soon the French were determined to restore the Pope. After a two-month siege, Rome capitulated on 29 June 1849 and the Pope was restored. Garibaldi and Mazzini once again fled into exile—in 1850 Garibaldi went to New York City. Meanwhile, the Austrians besieged Venice, which was defended by a volunteer army led by Daniele Manin and Guglielmo Pepe, who were forced to surrender on 24 August. Pro-independence fighters were hanged en masse in Belfiore, while the Austrians moved to restore order in central Italy, restoring the princes who had been expelled and establishing their control over the Papal Legations. The revolutions were thus completely crushed.

Morale was of course badly weakened, but the dream of Risorgimento did not die. Instead, the Italian patriots learned some lessons that made them much more effective at the next opportunity in 1860. Military weakness was glaring, as the small Italian states were completely outmatched by France and Austria.

France was a potential ally, and the patriots realized they had to focus all their attention on expelling Austria first, with a willingness to give the French whatever they wanted in return for essential military intervention. As a result of this France received Nice and Savoy in 1860. Secondly, the patriots realized that the Pope was an enemy, and could never be the leader of a united Italy. Third they realized that republicanism was too weak a force. Unification had to be based on a strong monarchy, and in practice that meant reliance on Piedmont (the Kingdom of Sardinia) under King Victor Emmanuel II (1820–1878) of the House of Savoy.

Cavour and the prospects for unification

Count Cavour (1810–1861) provided critical leadership. He was a modernizer interested in agrarian improvements, banks, railways and free trade. He opened a newspaper as soon as censorship allowed it: Il Risorgimento called for the independence of Italy, a league of Italian princes, and moderate reforms. He had the ear of the king and in 1852 became prime minister. He ran an efficient active government, promoting rapid economic modernization while upgrading the administration of the army and the financial and legal systems. He sought out support from patriots across Italy.

In 1855, the kingdom became an ally of Britain and France in the Crimean War, which gave Cavour’s diplomacy legitimacy in the eyes of the great powers.

Towards the Kingdom of Italy

The “Pisacane” fiasco

In 1857, Carlo Pisacane, an aristocrat from Naples who had embraced Mazzini’s ideas, decided to provoke a rising in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. His small force landed on the island of Ponza. It overpowered guards and liberated hundreds of prisoners. In sharp contrast to his hypothetical expectations, there was no local uprising and the invaders were quickly overpowered. Pisacane was killed by angry locals who suspected he was leading a gypsy band trying to steal their food.

The Second Italian Independence War of 1859 and its aftermath

Main article: Second Italian War of Independence

The Second War of Italian Independence began in April 1859 when the Sardinian Prime Minister Count Cavour found an ally in Napoleon III. Napoleon III signed a secret alliance and Cavour provoked Austria with military maneuvers and eventually led to the war in April 1859. Cavour called for volunteers to enlist in the Italian liberation. The Austrians planned to use their army to beat the Sardinians before the French could come to their aid. Austria had an army of 140,000 men, while the Sardinians had a mere 70,000 men by comparison. However, the Austrians’ numerical strength was outweighed by an ineffectual leadership appointed by the Emperor on the basis of noble lineage, rather than military competency. Their army was slow to enter the capital of Sardinia, taking almost ten days to travel the 80 kilometers (50 mi). By this time, the French had reinforced the Sardinians, so the Austrians retreated.

The Austrians were defeated at the Battle of Magenta on 4 June and pushed back to Lombardy. Napoleon III’s plans worked and at the Battle of Solferino, France and Sardinia defeated Austria and forced negotiations; at the same time, in the northern part of Lombardy, the Italian volunteers known as the Hunters of the Alps, led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, defeated the Austrians at Varese and Como. On 12 July, the Armistice of Villafranca was signed. The settlement, by which Lombardy was annexed to Sardinia, left Austria in control of Venice.

Sardinia eventually won the Second War of Italian Unification through statesmanship rather than armies or popular election. The final arrangement was ironed out by “back-room” deals instead of on the battlefield. This was because neither France, Austria, nor Sardinia wanted to risk another battle and could not handle further fighting. All of the sides were eventually unhappy with the outcome of the Second War of Italian Unification and expected another conflict in the future.

Sardinia annexed Lombardy from Austria; it later occupied and annexed the United Provinces of Central Italy, consisting of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Parma, the Duchy of Modena and Reggio and the Papal Legations on 22 March 1860. Sardinia handed Savoy and Nice over to France at the Treaty of Turin, a decision that was the consequence of the Plombières Agreement, on 24 March 1860, an event that caused the Niçard exodus, which was the emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy.

Main article: Expedition of the Thousand

Thus, by early 1860, only five states remained in Italy—the Austrians in Venetia, the Papal States (now minus the Legations), the new expanded Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and San Marino.[52][53][54]

Francis II of the Two Sicilies, the son and successor of Ferdinand II (the infamous “King Bomba”), had a well-organized army of 150,000 men. But his father’s tyranny had inspired many secret societies, and the kingdom’s Swiss mercenaries were unexpectedly recalled home under the terms of a new Swiss law that forbade Swiss citizens to serve as mercenaries. This left Francis with only his mostly unreliable native troops. It was a critical opportunity for the unification movement. In April 1860, separate insurrections began in Messina and Palermo in Sicily, both of which had demonstrated a history of opposing Neapolitan rule. These rebellions were easily suppressed by loyal troops.

In the meantime, Giuseppe Garibaldi, a native of Nice, was deeply resentful of the French annexation of his home city. He hoped to use his supporters to regain the territory. Cavour, terrified of Garibaldi provoking a war with France, persuaded Garibaldi to instead use his forces in the Sicilian rebellions. On 6 May 1860, Garibaldi and his cadre of about a thousand Italian volunteers (called I Mille), steamed from Quarto near Genoa, and, after a stop in Talamone on 11 May, landed near Marsala on the west coast of Sicily.

Near Salemi, Garibaldi’s army attracted scattered bands of rebels, and the combined forces defeated the opposing army at Calatafimi on 13 May. Within three days, the invading force had swelled to 4,000 men. On 14 May Garibaldi proclaimed himself dictator of Sicily, in the name of Victor Emmanuel. After waging various successful but hard-fought battles, Garibaldi advanced upon the Sicilian capital of Palermo, announcing his arrival by beacon-fires kindled at night. On 27 May the force laid siege to the Porta Termini of Palermo, while a mass uprising of street and barricade fighting broke out within the city.

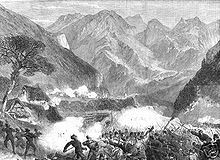

Battle of Calatafimi

With Palermo deemed insurgent, Neapolitan general Ferdinando Lanza, arriving in Sicily with some 25,000 troops, furiously bombarded Palermo nearly to ruins. With the intervention of a British admiral, an armistice was declared, leading to the Neapolitan troops’ departure and surrender of the town to Garibaldi and his much smaller army. In Palermo created the Dictatorship of Garibaldi.

This resounding success demonstrated the weakness of the Neapolitan government. Garibaldi’s fame spread and many Italians began to consider him a national hero. Doubt, confusion, and dismay overtook the Neapolitan court—the king hastily summoned his ministry and offered to restore an earlier constitution, but these efforts failed to rebuild the peoples’ trust in Bourbon governance.

Six weeks after the surrender of Palermo, Garibaldi attacked Messina. Within a week, its citadel surrendered. Having conquered Sicily, Garibaldi proceeded to the mainland, crossing the Strait of Messina with the Neapolitan fleet at hand. The garrison at Reggio Calabria promptly surrendered. As he marched northward, the populace everywhere hailed him, and military resistance faded: on 18 and 21 August, the people of Basilicata and Apulia, two regions of the Kingdom of Naples, independently declared their annexation to the Kingdom of Italy. At the end of August, Garibaldi was at Cosenza, and, on 5 September, at Eboli, near Salerno. Meanwhile, Naples had declared a state of siege, and on 6 September the king gathered the 4,000 troops still faithful to him and retreated over the Volturno river. The next day, Garibaldi, with a few followers, entered by train into Naples, where the people openly welcomed him.

Defeat of the Kingdom of Naples

Though Garibaldi had easily taken the capital, the Neapolitan army had not joined the rebellion en masse, holding firm along the Volturno River. Garibaldi’s irregular bands of about 25,000 men could not drive away the king or take the fortresses of Capua and Gaeta without the help of the Sardinian army. The Sardinian army, however, could only arrive by traversing the Papal States, which extended across the entire center of the peninsula. Ignoring the political will of the Holy See, Garibaldi announced his intent to proclaim a “Kingdom of Italy” from Rome, the capital city of Pope Pius IX. Seeing this as a threat to the domain of the Catholic Church, Pius threatened excommunication for those who supported such an effort. Afraid that Garibaldi would attack Rome, Catholics worldwide sent money and volunteers for the Papal Army, which was commanded by General Louis Lamoricière, a French exile.

The settling of the peninsular standoff now rested with Napoleon III. If he let Garibaldi have his way, Garibaldi would likely end the temporal sovereignty of the Pope and make Rome the capital of Italy. Napoleon, however, may have arranged with Cavour to let the king of Sardinia free to take possession of Naples, Umbria and the other provinces, provided that Rome and the “Patrimony of St. Peter” were left intact.

It was in this situation that a Sardinian force of two army corps, under Fanti and Cialdini, marched to the frontier of the Papal States, its objective being not Rome but Naples. The Papal troops under Lamoricière advanced against Cialdini, but were quickly defeated and besieged in the fortress of Ancona, finally surrendering on 29 September. On 9 October, Victor Emmanuel arrived and took command. There was no longer a papal army to oppose him, and the march southward proceeded unopposed.

Garibaldi distrusted the pragmatic Cavour since Cavour was the man ultimately responsible for orchestrating the French annexation of the city of Nice, which was his birthplace. Nevertheless, he accepted the command of Victor Emmanuel. When the king entered Sessa Aurunca at the head of his army, Garibaldi willingly handed over his dictatorial power. After greeting Victor Emmanuel in Teano with the title of King of Italy, Garibaldi entered Naples riding beside the king. Garibaldi then retired to the island of Caprera, while the remaining work of unifying the peninsula was left to Victor Emmanuel.

The progress of the Sardinian army compelled Francis II to give up his line along the river, and he eventually took refuge with his best troops in the fortress of Gaeta. His courage boosted by his resolute young wife, Queen Marie Sophie, Francis mounted a stubborn defence that lasted three months. But European allies refused to provide him with aid, food and munitions became scarce, and disease set in, so the garrison was forced to surrender. Nonetheless, ragtag groups of Neapolitans loyal to Francis fought on against the Italian government for years to come.

The fall of Gaeta brought the unification movement to the brink of fruition—only Rome and Venetia remained to be added. On 18 February 1861, Victor Emmanuel assembled the deputies of the first Italian Parliament in Turin. On 17 March 1861, the Parliament proclaimed Victor Emmanuel King of Italy, and on 27 March 1861 Rome was declared Capital of Italy, even though it was not yet in the new Kingdom.

Three months later Cavour died, having seen his life’s work nearly completed. When he was given the last rites, Cavour purportedly said: “Italy is made. All is safe.”

Roman Question

Main article: Roman Question

Mazzini was discontented with the perpetuation of monarchical government and continued to agitate for a republic. With the motto “Free from the Alps to the Adriatic“, the unification movement set its gaze on Rome and Venice. There were obstacles, however. A challenge against the Pope’s temporal dominion was viewed with profound distrust by Catholics around the world, and there were French troops stationed in Rome. Victor Emmanuel was wary of the international repercussions of attacking the Papal States and discouraged his subjects from participating in revolutionary ventures with such intentions.

Nonetheless, Garibaldi believed that the government would support him if he attacked Rome. Frustrated at inaction by the king, and bristling over perceived snubs, he came out of retirement to organize a new venture. In June 1862, he sailed from Genoa and landed again at Palermo, where he gathered volunteers for the campaign, under the slogan o Roma o Morte (“either Rome or Death”). The garrison of Messina, loyal to the king’s instructions, barred their passage to the mainland. Garibaldi’s force, now numbering two thousand, turned south and set sail from Catania. Garibaldi declared that he would enter Rome as a victor or perish beneath its walls. He landed at Melito on 14 August and marched at once into the Calabrian mountains.

Far from supporting this endeavour, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Pallavicino, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August the two forces met in the Aspromonte. One of the regulars fired a chance shot, and several volleys followed, but Garibaldi forbade his men to return fire on fellow subjects of the Kingdom of Italy. The volunteers suffered several casualties, and Garibaldi himself was wounded; many were taken prisoner. Garibaldi was taken by steamer to Varignano, where he was honorably imprisoned for a time, but finally released.

Meanwhile, Victor Emmanuel sought a safer means to the acquisition of the remaining Papal territory. He negotiated with the Emperor Napoleon for the removal of the French troops from Rome through a treaty. They agreed to the September Convention in September 1864, by which Napoleon agreed to withdraw the troops within two years. The Pope was to expand his own army during that time so as to be self-sufficient. In December 1866, the last of the French troops departed from Rome, in spite of the efforts of the pope to retain them. By their withdrawal, Italy (excluding Venetia and Savoy) was freed from the presence of foreign soldiers.

The seat of government was moved in 1865 from Turin, the old Sardinian capital, to Florence, where the first Italian parliament was summoned. This arrangement created such disturbances in Turin that the king was forced to leave that city hastily for his new capital.

Third War of Independence (1866)

Main article: Third Italian War of Independence

In the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, Austria contested with Prussia the position of leadership among the German states. The Kingdom of Italy seized the opportunity to capture Venetia from Austrian rule and allied itself with Prussia.[63] Austria tried to persuade the Italian government to accept Venetia in exchange for non-intervention. However, on 8 April, Italy and Prussia signed an agreement that supported Italy’s acquisition of Venetia, and on 20 June Italy issued a declaration of war on Austria. Within the context of Italian unification, the Austro-Prussian war is called the Third Independence War, after the First (1848) and the Second (1859).

Victor Emmanuel hastened to lead an army across the Mincio to the invasion of Venetia, while Garibaldi was to invade the Tyrol with his Hunters of the Alps. The Italian army encountered the Austrians at Custoza on 24 June and suffered a defeat. On 20 July the Regia Marina was defeated in the battle of Lissa. The following day, Garibaldi’s volunteers defeated an Austrian force in the Battle of Bezzecca, and moved toward Trento.

Meanwhile, Prussian Minister President Otto von Bismarck saw that his own ends in the war had been achieved, and signed an armistice with Austria on 27 July. Italy officially laid down its arms on 12 August. Garibaldi was recalled from his successful march and resigned with a brief telegram reading only “Obbedisco” (“I obey”).

Prussia’s success on the northern front obliged Austria to cede Venetia (present-day Veneto and parts of Friuli) and the city of Mantua (the last remnant of the Quadrilatero). Under the terms of a peace treaty signed in Vienna on 12 October, Emperor Franz Joseph had already agreed to cede Venetia to Napoleon III in exchange for non-intervention in the Austro-Prussian War, and thus Napoleon ceded Venetia to Italy on 19 October, in exchange for the earlier Italian acquiescence to the French annexation of Savoy and Nice.

In the peace treaty of Vienna, it was written that the annexation of Venetia would have become effective only after a referendum—taken on 21 and 22 October—to let the Venetian people express their will about being annexed or not to the Kingdom of Italy. Historians suggest that the referendum in Venetia was held under military pressure,[66] as a mere 0.01% of voters (69 out of more than 642,000 ballots) voted against the annexation.[67] However it should be admitted that the re-establishment of a Republic of Venice had little chances to develop.

Austrian forces put up some opposition to the invading Italians, to little effect. Victor Emmanuel entered Venice and Venetian land, and performed an act of homage in the Piazza San Marco.

Mentana and Villa Glori

The national party, with Garibaldi at its head, still aimed at the possession of Rome, as the historic capital of the peninsula. In 1867 Garibaldi made a second attempt to capture Rome, but the papal army, strengthened with a new French auxiliary force, defeated his poorly armed volunteers at Mentana. Subsequently, a French garrison remained in Civitavecchia until August 1870, when it was recalled following the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War.

Before the defeat at Mentana on 3 November 1867,[69] Enrico Cairoli, his brother Giovanni, and 70 companions had made a daring attempt to take Rome. The group had embarked in Terni and floated down the Tiber. Their arrival in Rome was to coincide with an uprising inside the city. On 22 October 1867, the revolutionaries inside Rome seized control of the Capitoline Hill and of Piazza Colonna. Unfortunately for the Cairoli and their companions, by the time they arrived at Villa Glori, on the northern outskirts of Rome, the uprising had already been suppressed. During the night of 22 October 1867, the group was surrounded by Papal Zouaves, and Giovanni was severely wounded. Enrico was mortally wounded and bled to death in Giovanni’s arms.

With Cairoli dead, command was assumed by Giovanni Tabacchi who had retreated with the remaining volunteers into the villa, where they continued to fire at the papal soldiers. These also retreated in the evening to Rome. The survivors retreated to the positions of those led by Garibaldi on the Italian border.

Memorial

At the summit of Villa Glori, near the spot where Enrico died, there is a plain white column dedicated to the Cairoli brothers and their 70 companions. About 200 meters to the right from the Terrazza del Pincio, there is a bronze monument of Giovanni holding the dying Enrico in his arm. A plaque lists the names of their companions. Giovanni never recovered from his wounds and from the tragic events of 1867. According to an eyewitness,[70] when Giovanni died on 11 September 1869:

In the last moments, he had a vision of Garibaldi and seemed to greet him with enthusiasm. I heard (so says a friend who was present) him say three times: “The union of the French to the papal political supporters was the terrible fact!” he was thinking about Mentana. He called Enrico many times, that he might help him, then he said: “but we will certainly win; we will go to Rome!”

Capture of Rome

Main article: Capture of Rome

In July 1870, the Franco-Prussian War began. In early August, the French Emperor Napoleon III recalled his garrison from Rome, thus no longer providing protection to the Papal State. Widespread public demonstrations illustrated the demand that the Italian government take Rome. The Italian government took no direct action until the collapse of the Second French Empire at the Battle of Sedan. King Victor Emmanuel II sent Count Gustavo Ponza di San Martino to Pius IX with a personal letter offering a face-saving proposal that would have allowed the peaceful entry of the Italian Army into Rome, under the guise of offering protection to the pope. The Papacy, however, exhibited something less than enthusiasm for the plan:

The Pope’s reception of San Martino (10 September 1870) was unfriendly. Pius IX allowed violent outbursts to escape him. Throwing the King’s letter upon the table he exclaimed, “Fine loyalty! You are all a set of vipers, of whited sepulchres, and wanting in faith.” He was perhaps alluding to other letters received from the King. After, growing calmer, he exclaimed: “I am no prophet, nor son of a prophet, but I tell you, you will never enter Rome!” San Martino was so mortified that he left the next day.

The Italian Army, commanded by General Raffaele Cadorna, crossed the papal frontier on 11 September and advanced slowly toward Rome, hoping that a peaceful entry could be negotiated. The Italian Army reached the Aurelian Walls on 19 September and placed Rome under a state of siege. Although now convinced of his unavoidable defeat, Pius IX remained intransigent to the bitter end and forced his troops to put up a token resistance. On 20 September, after a cannonade of three hours had breached the Aurelian Walls at Porta Pia, the Bersaglieri entered Rome and marched down Via Pia, which was subsequently renamed Via XX Settembre. Forty-nine Italian soldiers and four officers, and nineteen papal troops, died. Rome and Latium were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy after a plebiscite held on 2 October. The results of this plebiscite were accepted by decree of 9 October.

Initially the Italian government had offered to let the pope keep the Leonine City, but the Pope rejected the offer because acceptance would have been an implied endorsement of the legitimacy of the Italian kingdom’s rule over his former domain. Pius IX declared himself a prisoner in the Vatican, although he was not actually restrained from coming and going. Rather, being deposed and stripped of much of his former power also removed a measure of personal protection—if he had walked the streets of Rome he might have been in danger from political opponents who had formerly kept their views private. Officially, the capital was not moved from Florence to Rome until July 1871.

Historian Raffaele de Cesare made the following observations about Italian unification:

The Roman question was the stone tied to Napoleon’s feet—that dragged him into the abyss. He never forgot, even in August 1870, a month before Sedan, that he was a sovereign of a Catholic country, that he had been made Emperor, and was supported by the votes of the Conservatives and the influence of the clergy; and that it was his supreme duty not to abandon the Pontiff. For twenty years Napoleon III had been the true sovereign of Rome, where he had many friends and relations…. Without him the temporal power would never have been reconstituted, nor, being reconstituted, would have endured.[74]

Problems

Unification was achieved entirely in terms of Piedmont’s interests. Martin Clark says, “It was Piedmontization all around.”[75] Cavour died unexpectedly in June 1861, at 50, and most of the many promises that he made to regional authorities to induce them to join the newly unified Italian kingdom were ignored. The new Kingdom of Italy was structured by renaming the old Kingdom of Sardinia and annexing all the new provinces into its structures. The first king was Victor Emmanuel II, who kept his old title.

National and regional officials were all appointed by Piedmont. A few regional leaders succeeded to high positions in the new national government, but the top bureaucratic and military officials were mostly Piedmontese. The national capital was briefly moved to Florence and finally to Rome, one of the cases of Piedmont losing out.

However, Piedmontese tax rates and regulations, diplomats and officials were imposed on all of Italy. The new constitution was Piedmont’s old constitution. The document was generally liberal and was welcomed by liberal elements. However, its anticlerical provisions were resented in the pro-clerical regions in places such as around Venice, Rome, and Naples – as well as the island of Sicily. Cavour had promised there would be regional and municipal, local governments, but all the promises were broken in 1861.

The first decade of the kingdom saw savage civil wars in Sicily and in the Naples region. Hearder claimed that failed efforts to protest unification involved “a mixture of spontaneous peasant movement and a Bourbon-clerical reaction directed by the old authorities”.

The pope lost Rome in 1870 and ordered the Catholic Church not to co-operate with the new government, a decision fully reversed only in 1929.[77] Most people for Risorgimento had wanted strong provinces, but they got a strong central state instead. The inevitable long-run results were a severe weakness of national unity and a politicized system based on mutually hostile regional violence. Such factors remain in the 21st century.

Ruling and representing southern Italy

From the spring of 1860 to the summer of 1861, a major challenge that the Piedmontese parliament faced on national unification was how they should govern and control the southern regions of the country that were frequently represented and described by northern Italian correspondents as “corrupt”, “barbaric”, and “uncivilized” In response to the depictions of southern Italy, the Piedmontese parliament had to decide whether it should investigate the southern regions to better understand the social and political situations there or it should establish jurisdiction and order by using mostly force.

The dominance of letters sent from the Northern Italian correspondents that deemed Southern Italy to be “so far from the ideas of progress and civilization” ultimately induced the Piedmontese parliament to choose the latter course of action, which effectively illustrated the intimate connection between representation and rule.[81] In essence, the Northern Italians’ “representation of the south as a land of barbarism (variously qualified as indecent, lacking in ‘public conscience’, ignorant, superstitious, etc.)” provided the Piedmontese with the justification to rule the southern regions on the pretext of implementing a superior, more civilized, “Piedmontese morality”.[81]

Historiography

Italian unification is still a topic of debate. According to Massimo d’Azeglio, centuries of foreign domination created remarkable differences in Italian society, and the role of the newly formed government was to face these differences and to create a unified Italian society. Still today the most famous quote of Massimo d’Azeglio is, “L’Italia è fatta. Restano da fare gli Italiani” (Italy has been made. Now it remains to make Italians)

The economist and politician Francesco Saveria Nitti criticized the newly created state for not considering the substantial economic differences between Northern Italy, a free-market economy, and Southern Italy, a state protectionist economy, when integrating the two. When the Kingdom of Italy extended the free-market economy to the rest of the country, the South’s economy collapsed under the weight of the North’s. Nitti contended that this change should have been much more gradual in order to allow the birth of an adequate entrepreneurial class able to make strong investments and initiatives in the south. These mistakes, he felt, were the cause of the economic and social problems which came to be known as the Southern Question (Questione Meridionale).

The politician, historian, and writer Gaetano Salvemini commented that even though Italian unification had been a strong opportunity for both a moral and economic rebirth of Italy’s Mezzogiorno (Southern Italy), because of a lack of understanding and action on the part of politicians, corruption and organized crime flourished in the South.[85] The Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci criticized Italian unification for the limited presence of the masses in politics, as well as the lack of modern land reform in Italy.

Revisionism of Risorgimento produced a clear radicalization of Italy in the mid-20th century, following the fall of the Savoy monarchy and fascism during World War II. Reviews of the historical facts concerning Italian unification’s successes and failures continue to be undertaken by domestic and foreign academic authors, including Denis Mack Smith, Christopher Duggan, and Lucy Riall. Recent work emphasizes the central importance of nationalism.

Italian ethnic regions claimed in the 1930s by the Italian irredentism: * Green: Nice, Ticino and Dalmatia * Red: Malta * Violet: Corsica * Savoy and Corfu were later claimed

It can be said that Italian unification was never truly completed in the 19th century. Many Italians remained outside the borders of the Kingdom of Italy and this situation created the Italian irredentism.

The term risorgimento (Rising again) refers to the domestic reorganization of the stratified Italian identity into a unified, national front. The word literally means “Rising again” and was an ideological movement which strove to spark national pride, leading to political oppositional to foreign rule and influence. There is contention on its actual impact in Italy, some Scholars arguing it was a liberalizing time for 19th century Italian culture, while others speculate that although it was a patriotic revolution, it only tangibly aided the upper-class and bourgeois publics without actively benefitting the lower classes.

Italia irredenta (unredeemed Italy) was an Italian nationalist opinion movement that emerged after Italian unification. It advocated irredentism among the Italian people as well as other nationalities who were willing to become Italian and as a movement; it is also known as “Italian irredentism”. Not a formal organization, it was just an opinion movement that claimed that Italy had to reach its “natural borders,” meaning that the country would need to incorporate all areas predominantly consisting of ethnic Italians within the near vicinity outside its borders. Similar patriotic and nationalistic ideas were common in Europe in the 19th century.

Irredentism and the World Wars

Italy entered into the First World War in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence,[91] in a historiographical perspective that identifies in the latter the conclusion of the unification of Italy, whose military actions began during the revolutions of 1848 with the First Italian War of Independence.

During the post-unification era, some Italians were dissatisfied with the current state of the Italian Kingdom since they wanted the kingdom to include Trieste, Istria, and other adjacent territories as well. This Italian irredentism succeeded in World War I with the annexation of Trieste and Trento, with the respective territories of Julian March and Trentino-Alto Adige.

The Kingdom of Italy had declared neutrality at the beginning of the war, officially because the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary was a defensive one, requiring its members to come under attack first. Many Italians were still hostile to Austria’s continuing occupation of ethnically Italian areas, and Italy chose not to enter. Austria-Hungary requested Italian neutrality, while the Triple Entente (which included Great Britain, France and Russia) requested its intervention. With the Treaty of London, signed in April 1915, Italy agreed to declare war against the Central Powers in exchange for the irredent territories of Friuli, Trentino, and Dalmatia (see Italia irredenta).

Italian irredentism obtained an important result after the First World War, when Italy gained Trieste, Gorizia, Istria, and the city of Zara. But Italy did not receive other territories promised by the Treaty of London, so this outcome was denounced as a “Mutilated victory“. The rhetoric of “Mutilated victory” was adopted by Benito Mussolini and led to the rise of Italian fascism, becoming a key point in the propaganda of Fascist Italy. Historians regard “Mutilated victory” as a “political myth”, used by fascists to fuel Italian imperialism and obscure the successes of liberal Italy in the aftermath of World War I.

During the Second World War, after the Axis attack on Yugoslavia, Italy created the Governatorate of Dalmatia (from 1941 to September 1943), so the Kingdom of Italy annexed temporarily even Split (Italian Spalato), Kotor (Cattaro), and most of coastal Dalmatia. From 1942 to 1943, even Corsica and Nice (Italian Nizza) were temporarily annexed to the Kingdom of Italy, nearly fulfilling in those years the ambitions of Italian irredentism.

For its avowed purpose, the movement had the “emancipation” of all Italian lands still subject to foreign rule after Italian unification. The Irredentists took language as the test of the alleged Italian nationality of the countries they proposed to emancipate, which were Trentino, Trieste, Dalmatia, Istria, Gorizia, Ticino, Nice (Nizza), Corsica, and Malta. Austria-Hungary promoted Croatian interests in Dalmatia and Istria to weaken Italian claims in the western Balkans before the First World War.

After World War II

After World War II, the irredentism movement faded away in Italian politics. Under the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947, Istria, Kvarner, most of the Julian March as well as the Dalmatian city of Zara was annexed by Yugoslavia causing the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus, which led to the emigration of between 230,000 and 350,000 of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), the others being ethnic Slovenians, ethnic Croatians, and ethnic Istro-Romanians, choosing to maintain Italian citizenship.

Main article: Anniversary of the Unification of Italy

Italy celebrates the anniversary of the unification every fifty years, on 17 March (the date of proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy). The anniversary occurred in 1911 (50th), 1961 (100th), 2011 (150th) and 2021 (160th) with several celebrations throughout the country. The National Unity and Armed Forces Day, celebrated on 4 November, commemorates the end of World War I with the Armistice of Villa Giusti, a war event considered to complete the process of unification of Italy.

Calitri Surnames from the 1500’s

The following is an excerpt from the History of Calitri by Vito Acocella which appears in another section of this Ancestry. The excerpt lists more than 250 Surnames that lived in Calitri in the early 1500’s. Anyone reading this topic for the first time, and assuming they have ancestry in Calitri, should take a look at the alphabetically organized names. Consider that the spelling of some surnames has changed, and it may be of interest to review all of the names. Also, consider that different spellings from current versions of that name, could in fact be the same family. As example, the name “DiCosmo” in Calitri in the 1500’s was sometimes changed to “DeCosmo” in the United States. Therefore, a search for DeCosmo would not be found on the following list.

This information from the names in this list is a particularly revealing and is a significant resource. Many of these names have survived to the current time in Calitri and are widely planted into many cities in the United States.

Following is a partial list of some of the Calitrani surnames that are related to the Nannariello family. Some of these names listed could go back more than four hundred years. Again, this is a partial list that has evolved from marriages across four centuries or so, in a village that had minimal attrition among nearby villages and provinces.

Cerreta, Cestone, Borrillo, Bozza, DiGernonim, Di Maio, Di Napoli, Galgano, Germano, Lampariello, Lodrusco, Lupo, Maffucci, Maglione, Melaccio, Martiniello, Russo, Sabbi, Toglia, Tozza

Direct Quote from the History of Calitri.

Archives in Naples, I have been able to get the names of the following families existing in the second half of the sixteenth century and in the first decades of the seventeenth century, which are hereby stated in alphabetical order:

Abruzzese; Albanese; Amatiello;; Araneo; Autieri; Balascio’ Barbato; Barrata; Baviera; Bianco; Borbone; Borea; Borrello (later on, Borrillo, Berrilli); Boscaglia; Bottigliero; Brigliaro; Bucco; Calcagno; Caldaro; Calvi; Cannaviello; Caposele and De Capossele; Caputo; Capuzza; Caradonna; Carcasio; Carlucci; Carpinelli; Carrieri; Caruso; Cssiero; Cataro; Cazzotta; Cegnaro; Cennarulo; Cera; Ceriello; Cerminiello; Cerrata; Cerreta; Cesta; Cestone; Ceva; Cialeo; Cicoyra, Cicoira, and also de Cicoira; Cicoria; Cioglia; Cioglia; Cocozza . Codella; Coviello; cuorpo; De Alifi; DeLoisi; De Belardino; De Blasi; De Calabritto. De Canio, De Carlo, De Cazzecarella (this seems to be a nickname.); De Corbo, De Colantuono; De Ferrante; De Feo; De Frecento; De Furno; De Giorgio; De Iandella; De Lillo; De Luciano; Del Barbiero; Cel Cogliano; Dell’Abbadia and Della Badia; Dell’Auletta; Della Pergola; Della Salvitelle; Delli Liuni; Dello Cilento; Dello Cossano; Dello Massaro; Dello Todisco; Della Valva; De Maio and Di Maio and also De Mayo; De Marsico; De Mauro; De Milia and Di Milia; De Minico; De Nicola; De Palo; De Prospero; De Rapone; De Rienzo; De Roberto; De Rosa; De Rubino; De Vintanni (Nickname); De Boezio and Boezio; Di Cairano and Di Cayrano; Di Carbonara; Di Cecca and De Cecca; Di Ciarlo; Di Conte; Di Cosmo; Di Meo; Di Muro; Di Napoli; Di Nora and De Nora; Di Porcello and Porcello; Di Quiqui; Di Teora; Dragnontto; Fata; Fastigio; Ferriero; Fierravante; Fiorention; Frasca; Frecchione; Frangione; Freda; Fruccio; Gala; Galgano; Gallucci; Gaurieri; Germano; Gervasi; Grieco; Ianella; Iannolillo; Innnuzzella; Incarnato; Iattariello; Insegnola; Iulianello; Lantella; Leone; Lombardo; Lucrezia; Lungaro; Lupone; Mafferecchia; maffuccio; Mangialardo; Margotta; Martinelli and Martinello; Martino; Marzullo; Melaccio; Metallo; Mucciaccio; Nannariello; Orlando; Paladino; Panaro; Parisi; Pasqualicchio; Paolantonio; Percaccino; Pasciuto; Pauloccia; Peccerillo Giuseppi di Pede di Caulo (nickname); Pedone; Pennetta; Petragalla; Pignone; Pinto; Polestra and Della Polestra; Porciello; Quaglio; Quaranta; Rabasca; Rago; Ranaldo (following, Rinaldi); Ricciardella; Ricciardi; Ricciardone; Rapolla; Radoaldo; Rapone; Rosa; Rotondo; Ruggiero and Ruggieri; Russo; Rustico; Sacchitella; Savanella and Savinella; Salvante; Sansonetto; Santoro; Scarricino; Scoca; Simone; Sepe; Sozio; Speranza; Strangia; Sterlicchio; Stigliano; Marino; Marino Stupolo alias vignaruolo (nickname); Sciatamarra; Tartaglia; Tornillo; Toglia; Torciano; Tozzolo; Tuozzolo; Vallata; Veglione; Vernecchia; Vitamore; Voccardo; Volpe; Zabatta; Zarrillo; Zampaglione; Zuglio.”

Calitri Earthquake of 1910

Charlie Nannariello shared some interesting oral history with his sons, Louis and Richard, possibly in the late 1940’s. He recalled his maternal Grandparents being killed in an earthquake but provided minimal information about the circumstances and the date. Later it was discovered that Canio would have been about nine years old when this occurred , and his grandparents lived on the same street his parents lived.

Calitri is in an earthquake zone that runs north and south along the central spine of Italy and the Apennines mountains. Calitri has suffered many earthquakes over the centuries. The earthquake that Charlie referred to occurred on June 7, 1910, when he was seven years old. His grandparents were Canio Martiniello and Rosa Bozza Martiniello, the father and mother of his mother, Francesca Martiniello Nannariello.

Following is the account of the earthquake from History of Calitri written by Vito Acocella, an Italian priest from Naples. It was Vito’s visit to Calitri shortly after the 1910 earthquake that motivated him to write this comprehensive history of Calitri. Canio’s grandparents were named in the Vito Acocella’s history along with the event of their being killed in their home during the earthquake.

Following is the verbatim account of the 1910 earthquake from the History of Calitri. Please note that the entire History of Calitri book is included in this Ancestry.

The frequency of the earthquakes, which almost periodically have hit our city, in addition to transforming the exterior aspect, has dispersed or destroyed every trace of antiquity. The final few vestiges – still surviving –fell with the earthquake of June 7, 1910, of which Calitri was the epicenter, and it stretched out for a radius of twenty kilometers. Preceded and accompanied by flashes of light, at 3:08 a seismic shock was noticed, first it was wave-like, then tremor-like. All the habitations were violently shaken. The people, seized by panic, left their houses at the first shock, in search of refuge in the open. Other earth shocks, which were lighter, were felt to continue at various intervals. Greatly damaged and with a more relevant number of victims was the upper part of the village, which was near the ruins of the collapsed castle. Here, the violence of the shocks had made fall «part of the revetment of support to the terraces of the old castle – as the Relazione [report] drawn up by Engineer Solimene, the fire chief, states; – but the walls that fell on the north side, where the hill was sheared off, ended up in the countryside below, while only two tracts at the corner of such wall on the south side of the hill, while falling, went to crush two houses, one built on ground level and the other above. And it is at this site that there was the major percentage of human victims.

The circle of pain was not just limited to the Rione Castello [Castle district], but it hit sporadically other areas of the habitat, where death was even more merciless. Uniquely pitiful was the fate that befell the Basile family, near the Church of the Immaculata, where the blind force of nature engulfed three beautiful girls in the debris, who were from fifteen to twenty years old. These were Maria Michela, Maria Antonietta and Grazia – who were found close, lifeless, in the jaws of death. Not too far away, three cute children, still in their cradle – Michele, Canio Vincenzo, and Raffaele Lampariello – were suffocated by heaps of rubble and stones. The married couple Canio and Rosa Martinello, who lived Sopra Corte, were overcome by the violence of the shock and thrown from the third floor to the ground. Elsewhere, Angelo Cestone, his wife and three children perished. In all, the number of victims rose to forty.

The first moment of panic having passed, the most courageous people carried first aid to those hit by the misadventure; but their work was ineffective or very limited because of inexperience or because of lack of suitable tools. The first true help was brought by some workers of the Acquedotto Pugliese, who, ready to volunteer themselves, hastened, under the direction of their engineers, to begin the unearthing of some survivors that were still alive. A company of the 64th infantry from near Bisaccia reached the area after a few hours, in order to keep order. The same day, other first aid teams from Lioni, Montella, Avellino, and from other neighboring villages arrived. It was a generous offer of human solidarity. Towards evening, from Naples, forty firemen and some fontaniere arrived and who were under the command of Engineer A. Silimene. These people threw themselves into the task of helping both with unearthing the bodies from the debris and with demolishing the unstable walls.

Exceedingly effective was the work of the Croce Rossa Italiana [Italian Red Cross], which arrived with a well-equipped train, under the direction of four doctors and twenty nurses. There also came a section of the Civil Engineer Corps, to organize the more urgent work of removal, of propping up and whatever else was necessary for the safety of the citizens. To such an end, there was demolished the highest part of the terraces of the ruined castle, which had caused, in their falling the greatest number of victims. In addition, with the walls of the terraces was demolished the top of the mountain, which from an altitude of 665 meters was brought to an altitude of 651 meters.[1] Therefore, following such demolition, and there was no more worry about the safety of the citizens, the surviving walls «of that tower made obscure by the centuries »did not cause any worry for the safety of the citizens.

[1] The altitude data, referred to here, was kindly furnished by an engineer of the Società «Ercole Antico», contractor for the work of the Acquedotto Pugliese – who, in 1911, came to Calitri to carry out the surveys and the studies for the branch line of the acqueduct into the habitat.

The population, terrified, were quartered in tents in the surrounding countryside or went back into the rural homes, of which our territory is full. Nightmare and dejection overcame everybody. Nor did this state of mind cease with the arrival of King Vittorio Emanuel III and Queen Elena, who, for the first hours of day No. 8, brought a word of comfort and abundant aid material. Solicitous was, also, the great interest of the Minister of Public Works the Honorable E. Sacchi, who provided for the approval of a LeggeSpeciale [Special Law], on the strength of which was given to those damaged favorable mutui [loans] with the Banco di Napoli for reconstruction and repair. In such a way, the building will also be improved. For those who remained homeless, a small district of aseismic homes, outside of the habitat.[1] But the major benefit that the population had, because of this disastrous earthquake, was a vast square, in the center of the village, due to the excavation that was done of the embankment, on which – up until 1883 – rose the parish church. Following, because of the Podestà, Emilio Nicolais son of the late 119 Sigismondo, in 1934 – 35, the square was remarkably expanded and harmonized with the new façade of the municipal building.

[1] There was another earthquake on July 23, 1930, which caused only slight damage in Calitri. The first shock was noticed on July 23, at 1:10AM; other shocks of minor intensity followed.

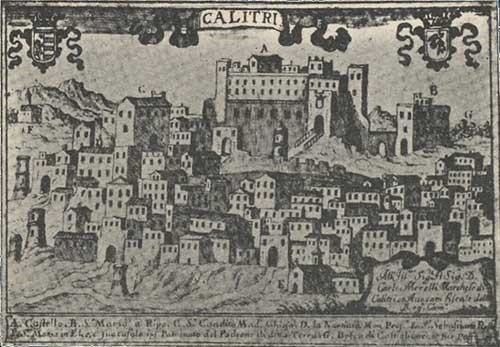

Calitri Castle

The castle on top of Calitri has always been a major part of its history, when it stood tall and the occupants ruled the village of Calitri. It was destroyed over time by several earthquakes and now lays in ruins. The following excerpt is from Vito Acocella’s History of Calitri.

Enfeoffment of the Ludovisi house. – Sale of the fief to Francesco Mirelli – description of the castle as it was in the last twenty years of the seventeenth century – Calitri, walled Terra with four gates.

Isabella Gesualdo, heiress to all the fiefs of her family, as has already been stated, was married to Nicolò Ludovisi, of Bologna, nephew of Pope Gregory XV. Only one daughter, Lavinia, was born of this marriage and she inherited all the maternal property at the death of her genitrice [mother], which took place on May 8, 1629. Soon afterwards, Lavinia also died; and, not having offspring, her many fiefs devolved upon the Crown. Nicolò Ludovisi, father of Lavinia, on May 16, 1636 bought the total estate for a large sum of money, and so, in this manner, he took possession of all the other property of the house of Gesualdo.

Nicolò Ludovisi, having died on December 24, 1664, left his property to his son Giambattista. Nothing is known of the new feudal lord with respect to our Comune. It is only necessary to remember that, although he had many and important fiefs in various regions of Italy, he preferred the Castle of Calitri for his usual residence. And in this castle he was pleased to host illustrious personalities among whom was the Archbishop of Conza, Iacopo Lente, who, «urged on by the prayers of prince Ludovisi, came to Calitri, was received cordially, and was always treated with great kindness.»[1]

[1] Ughelli, Italia Sacra (Ed. Coleti), vol VI, page 826. Archbishop Lente died on August 30, 1672, during his stay in Calitri, and was buried in the Chiesa-Madre [mother church].

Meanwhile, Giambattista Lodovisi, who was caught up in growing economic difficulties and compelled by his creditors, found it necessary to sell the fief of Calitri to Francesco Mirelli for the sum of thirty thousand eight hundred ducats. The contract was drawn up on February 13, 1676. But soon afterwards, Ludovisi, believing himself deceived in the value of the fief, sent his faithful Ingegnere [engineer] Antonio Chianelli, in secret, to Calitri. The engineer reported the true state of preservation of the castle and the earnings and liabilities of the fief. Chianelli reached Calitri in December of 1692 and, after having observed and investigated everything, wrote a very detailed Relazione [report], which is an extremely valuable document because of its historical data and because of the economic observations it contains.[1] On the basis of Chianelli’s report, Prince Lodovisi no longer opposed the sale and, with the deed of May 6, 1693, ratified the sales contract in favor of Francesco Mirelli.

[1] State Archives in Naples, privilegorium del Collaterale, volume 607, page 63-66.

The new feudal lord was a member of the Neapolitan nobility and his wife was Anna Paternò. From this marriage was born Carlo, who was a man of vast legal culture and had the high post of avvocato fiscale della R. Camera della Sommaria [Tax lawyer for the Supreme Administrative chamber of the Neapolitan kingdom.] Then, Francesco Mirelli, the new feudal lord, as soon as he had signed the definitive sales instrument, moved with his family into the vast and sumptuous castle of Calitri. The small fort had become truly magnificent because of the care of the rich and powerful Gesualdo lords, who had lived there for centuries and provided the castle with a system of defenses as well as every comfort, enabling them to live a refined and luxurious life.

The historian Pacichelli bore witness to the external shape of the castle, which he called imposing and grandiose, and he told of a precious engraving of the time — which is today very rare — in which is also reproduced the habitats and the other appurtenances of the «famous castle,» as he himself called it.[1] Moreover, other contemporary authorities highlighted the merits and the more salient characteristics of the inside and the exterior aspect of the castle: «A very famous castle, — wrote Castellano in the Cronica Conzana [Conzan Chronicle] after the visit he paid in 1691 — with about 300 rooms, which can comfortably accommodate five Courts of Nobles. The castle is equipped with two drawbridges with beautiful bastions, is atop a mountain, equipped with all the conveniences, and other….». The castle, which was architecturally imposing, was a very formidable instrument of defense. The castle was high, solid, and equipped with all the means of fortification and, as Chianelli – who visited it at the end of 1692 – writes «at first sight it seemed to me to be a well-built machine.» The lynchpin of the whole defensive system it seemed was constituted by the castle keep, which was rectangular, and made of enormous, solid wall with very few openings. Four large towers, equipped with feritoie [arrow slits] caditoie [drains through which to pour boiling oil on the assaulting troops] guaranteed the safety of the little fort, on which blockhouses, small towers, and other fortifications completed its wartime armor. Access to the castle, which was narrow and placed on the frontispiece or pediment, was assured with a solid drawbridge. The castle did not lack subterranean passage, which was well disguised, and which led into an open field that was outside of the surrounding wall of the village and properly below the modern strada di Piero, according to the tradition and the testimony of some of the ruins.

[1] G. D. Pacichelli, [TN: The internet gives his name as Giambattista Pacichelli] The kingdom of Naples in perspective, Naples, 1703, volume I, page 254

Inside the small fort, then, there were well-equipped armories, vast kitchens jam-packed with colossal storerooms and whatever else was necessary for the sumptuous life of the lord, from the wine cellar to the granary to the cisterns.[1] The luxurious salons and the richly appointed feudal family living quarters are especially interesting. In brief, «One can deduce the magnificence and grandness — observes Vinaccia — by the vastness of the plant, which truly shows it to have been a very magnificent castle.» In valid support of the small fortress, on a rough terrain, arose its external defenses, which consisted of bastions and a wide moat that girdled solid, battlemented walls, which surrounded it up to the Ripe [steep banks], where rose the little church of St. Maria ad Ripam.

[1] The bottom of a large cistern still remains. It can be seen by ascending a stepped incline in front of the chapel of the Madonna delle Grazia, on the via Castello.

Almost attached to the wall surrounding the castle rose the habitations of the citizens, which were extremely wretched and which constituted the Terra, a name that still survives today, as in the dialectical directions «ngimma a la Terra» [above the Terra (ngimma = [in cima a] sopra = above)] and the other direction «fore Terra» [fore = fuori = outside, that is, outside the Terra of Calitri.] etc. Around the fortilizio [small fortress], then, were clustered the habitations which, because of the needs of the growing population, developed along the slopes of the mountain, forming a compact and overlapping cluster, in the shape of an amphitheater, which Castellano — who visited Calitri in 1691when it had just 1843 inhabitants — described in this manner: «Calitri is situated in a high and elevated place, with a good construction of houses, which are all built in perspective, that is the windows are all on one side, that is on the lower part and the doors all on the upper part; so that from the road, which comes from Le Puglie[1], there is a beautiful theatrical perspective, to the point that the Illustrisimo Prince of old Venosa [and baron of Calitri], when he wanted to show his noble guests a beautiful sight, had lights put in said windows at night, which were a wonderful and peaceful sight.» For greater safety in the defense of the castle, the feudatori had the village surrounded by a solid wall: «the Terra is all walled in with four gates that make it very secure,» one reads in the Cronica Conzana, which has been cited many times.

That the habitat of Calitri was ringed by a solid wall with four gates for communication with the outside, can be shown no only from the incisione in prospettiva [The perspective drawing or etching] of the seventeenth century [which is reproduced above (TN: unable to put in this book, but it is in the Italian version)], but also from the surviving names of the gates, and from the ancient Itinerario delle processioni, [Procession itinerary] which is preserved in the parish archives.[1] The surrounding wall was started at the Torre district – where rose a massive keep – and headed toward the south, interrupted by the Porta di Nanno;[2] from here one descends still to the south until one is above the so called Pozzo Salito, to the north east of which opened precisely the Porta del Pozzo Salito; then one turns to the east, for a long stretch, up to the Porta del Buccolo[3]; then it continued downstream in order to go back up to the Posterla, where one finds oneself at the Porta of the same name. Here, the enclosing wall stops in order to give way to the impervious precipice of the Ripe [steep cliffs], which constituted a natural defense up to the castle. The four gates were defended, in their turn, by equally massive and round towers that watched over the entrance to the village like sentinels. This is, in its architectural and military lines, the structure of the castle and the walled perimeter of the habitat, as it appears in the second half of the seventeenth century, when the fief was sold to Francesco Mirelli.

[3] The porta del Buccolo corresponds today to that narrowing of the wide stepped road that from the piazzetta [little square] del Buccolo which leads upstream, before turning onto the road that leads to the Chapel of San Antonio Abate. It is called Viccolo, from Biccolo [=Bocca, mouth], because near there, outside the ring of the wall, there was a bocca or fosso [ditch] in which one threw garbage.

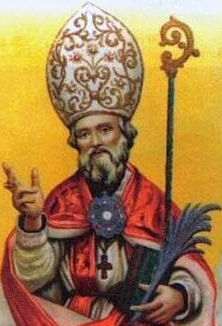

Calitri Patron Saint Canio

Canio Nannariello was named after his maternal grandfather, Canio Martiniello. His grandfather was named after the patron saint of Calitri, called Saint Canion or Saint Canio. When the traditions and obligations of naming sons after their fathers or grandfathers was exhausted, the tradition of naming a son after the Patron Saint was always very appropriate. Many Italians got their American names by a literal translation of the name, such as Giuseppe is Joseph and Guglielmo is William and so on. Canio became Charlie, when he came to the United States. which everyone called him. In Italian, Carlo would be the equivalent of Charles in English, but this is not the case for Canio. There is no oral or anecdotal history of how Canio became Charlie.

We are indebted to the History of Calitri book by Vito Acocella for an exploration of the facts and legends associated with Saint Canio. Some of the facts and traditions become obscured, but the story is fascinating and interesting.

Following is a verbatim portion of Chapter III of the History of Calitri.

Nothing out of the ordinary is revealed from the few contemporary sources that tell of the long Lombard domination in Calitri, whose few historic events, because of lack of documentation and physical remnants of that era, remain as if they were wrapped in the thick darkness of the middle ages. In addition, it is not difficult to understand the reasons for it, if one considers that because of the limited political and social importance of the castrum, the civil and administrative life of that village or — to use a Manzonian expression — of that “molehill of huts that arose at the foot of the castle. ” was also limited. However, where we lack history, we still have tradition, at whose base is always hidden an event of long ago, which event is transformed or embellished by the imagination of that great poet that is the people. History itself, when duly taking into account all the manifestations of the spirit of a people, cannot not also learn from traditions that have remained or have been passed down from age to age in song and story.

These traditions, however, need to be interpreted and revived: Manzoni observes, «chi non le aiuta, da sè dicon sempre troppo poco [who does not help them, by themselves they always say too little].» Such traditions, then, acquire greater prominence when they refer to religious feeling, which feeling has then considerable moral value for the people. In addition, one tradition in particular, which is very wide spread among the people, has been passed down to us over the centuries. The tradition states that a pious party – while transporting the body of the Saint Bishop Canion from Atella of the Campania to Acerenza and accomplishing the trip in small stages, as the length of the walk and the impassable nature of the place demanded – passed through the immediate vicinity of Calitri, where they stopped, attracted by the festive and uninterrupted sound of the bells.

The religious community of Calitri, seeing in that spontaneous sound the sign of a revelation, wanted to adopt the saint bishop as their patron, whose phalanx of a finger they retained as an acknowledgement of such an amazing event. This is what the pious tradition states, a tradition that – without specifying either the time or the persons involved – we Calitrani have, many times, heard from the lips of our mothers, who told it with the fervor of faith and with the certainty that it was historically accurate. This tradition is still alive in our people.

What brings such a tradition to mind, albeit embellished by the imagination of a people who have handed it down to us for many generations. Undoubtedly, at the basis of such a tradition, there is hidden a page of history with a specific time and person and which historical page is stripped of any legendary embellishment. It is historically certain that the Archbishop of Acerenza, Leone, having learned that ¾ at Altello della Campania ¾ «the body of Saint Canio was being treated irreverently and without any veneration», went to Altello in 799 with a party of pious persons and, in the fervor of his apostolic ministry, exhumed the holy body and led it in a procession to Acerenza, where he proclaimed it the patron of the Lucan city. The move took place during the domination of the Lombards, who favored the spread of the religion and the external practice of worship by any means.

At that time, the only wide road that led from Campania to Lucania, — where Acerenza lay — was the military road, which was built by the Lombards and which road went from one headquarters of theirs to another. The pious party had to follow this great road, and, moving from rest stop to rest stop in its long walk, made a rest stop in the immediate vicinity of Calitri. An important detail of this same tradition is stated to confirm this trip, and this detail is acknowledged in a local place name. It is a slightly vague sign, but nonetheless interesting for anyone who knows how to interpret it. The tradition, then, says that the party of the archbishop Leone stopped in sight of the village, in the Limunti district, placing the urn containing the holy body on a large white rock, while the bells of Calitri were ringing.

From then on, that large white rock took the very meaningful name — which it has kept until now — of Pietra di S. Canio [Rock of Saint Canio]. It is a simple name, and yet it encompasses a great deal of historic value! That large rock placed in the open countryside encapsulates a page of local religious history! If it is true that respondent nomina rebus,[the thing answers to its name] any doubt that may arise from the examination of this tradition is eliminated by the testimony of this local place name, which is a historical source.

If one wishes to discover the course of a river, one must go back to the source of that river, and, analogously, it is proper here to go back centuries in order to reconstruct, from historical sources, the figure of Canion, bishop and martyr, that – as a modern Bollandi writes –la legend l’acomplétemente difiguré. Canion, of African nationality, was bishop in a coastal region of that Dark Continent, who in the early centuries, was converted to the Christian religion. This is clear and is taken from history; only the life of the saint bishop and the details of the martyrdom remain wrapped in shadows, above all where it concerns the time in which he lived, the seat of his diocese in Africa, and the year of his martyrdom. We will try to tear away a little of this thick veil. The only source of information on our saint consists of an anonymous hagiography with the title Acta Sancti Canionis, which the strict Bollandist Enschenio, using very negative criticism, has judged «Suspicious, completely mythical, and the fruit of an uncertain and popular tradition.»

Almost nothing then, can one accept of what is reported in the Acta Santi Canionis, not even the name of the Episcopal seat which is called Iuliana, because no city of such a name – Enschenio noted – has ever been recorded by the geographers of Africa. The Bollandist focused on a detail reported by a very old ecclesiastical historian, Vittore Vitense, who relates that, when by order of Unnerico, [Huneric] king of the Vandals, all the bishops met in Carthage on February 1, 484 to give testimony to the faith professed by them, Pascasius Tulanensis, Pascasio bishop of Tulana was there. The Bollandist focused his investigation on this and concluded that Tulana is precisely the Episcopal seat of Canion; and he adds that «Pascasio could have been the successor of Canion, who was already expelled with his companions in the year 438 or even much later, if that expulsion took place much later.»