Mario Toglia has published three books about the Calitrani from Calitri, Italy who immigrated to the United States starting in the late 1800’s and during the first several decades of the Twentieth Century and beyond. These books are available from the Publisher Xlibris on their website, Xlibris.com and by Telephone 888 795 4274.

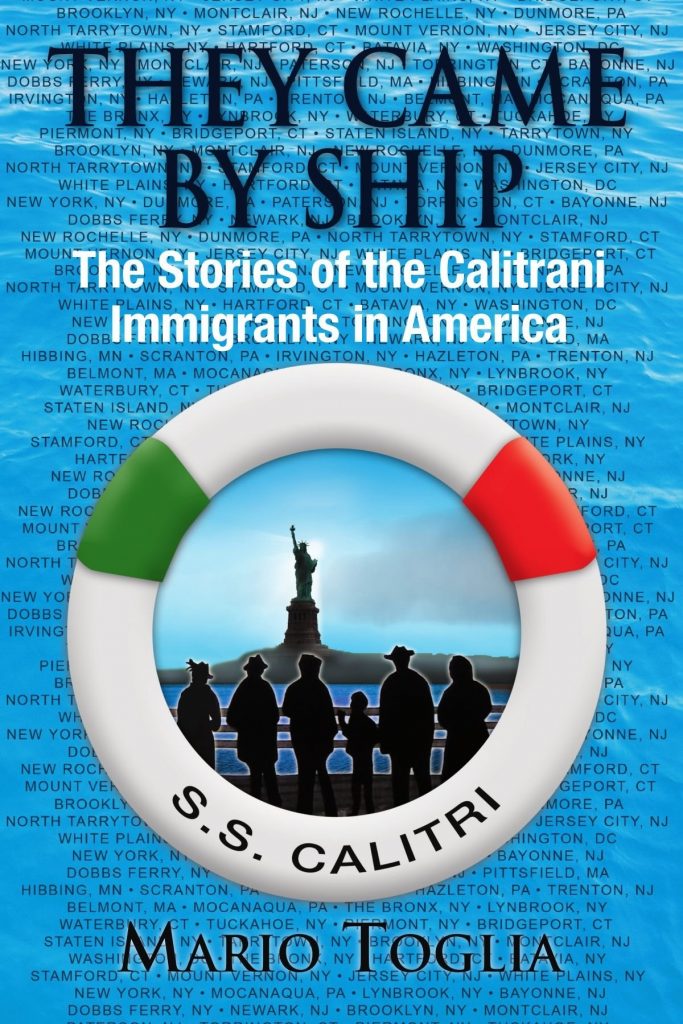

- They Came on Ships by Mario Toglia

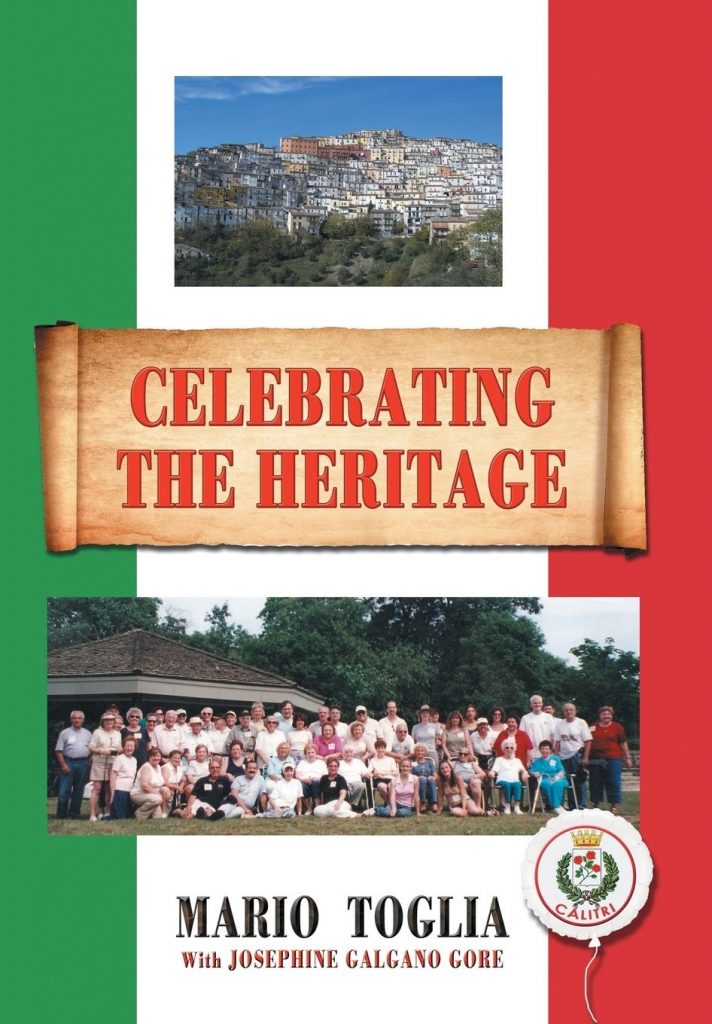

- Celebrating the Heritage by Mario Toglia with Josephine Galgano Gore

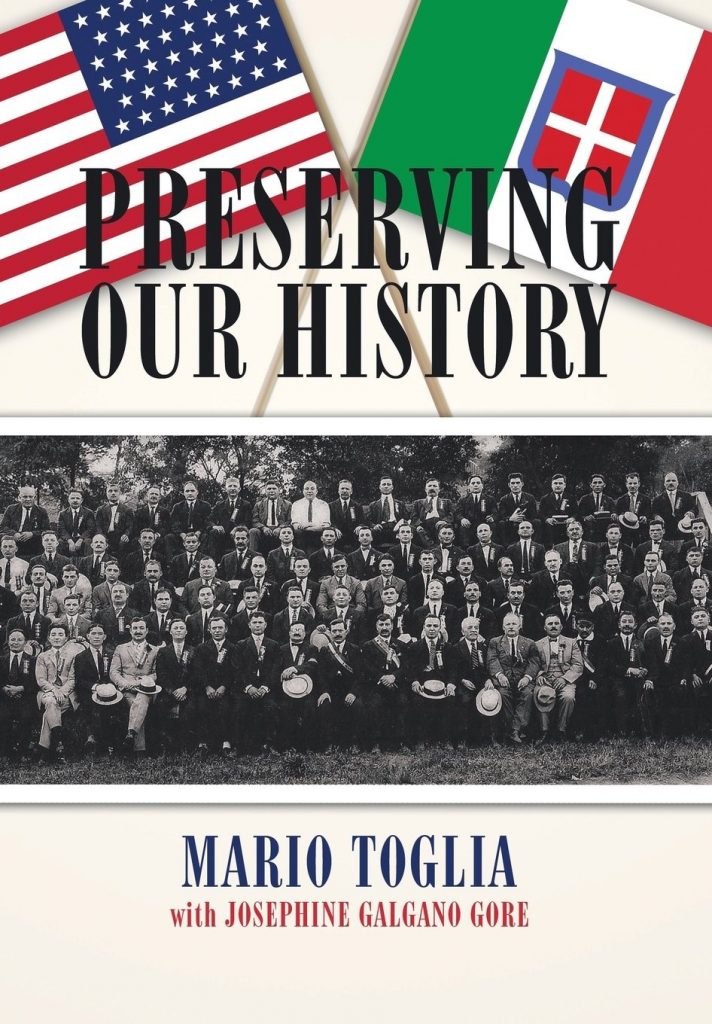

- Preserving our History by Mario Toglia with Josephine Galgano Gore

Anyone having more than a casual interest in Calitri and the immigration of Calitrani to the United States, would do well to review the books on the publisher website to determine if there is an interest in purchasing the books. The books provide a comprehensive history of the immigration and a unique insight into how the Calitrani adapted and survived in United States. To quote Mario Toglia, “it became obvious that it was m generation’s mission to honor and preserve the immigrant history and legacy of Calitri.”

Mario Toglia is an historian, an Italian heritage ancestry expert, a genealogist, and a gifted writer. He has used his broad interest and knowledge to focus specifically on the town of Calitri, Italy, where his family ancestry roots reside. Mario has assembled a team and researched and documented this immigration story in his books to an extraordinary level of detail.

The Mario Toglia team consists of Josephine Galgano Gore; Mary Basile Margotta, Angela Cicoira Moloney, Fred Rabasca, Richard Morris.

Mario Toglia’s books have inspired others to explore the Calitrani Ancestry. Calitri may possibly be the best documented emigration story from an Italian small town to the United States or for that matter, a town of any size in Italy.

Mario’s books were a major motivation for conceiving and building this website, and his inspiration and research support were significant.

Mario Toglia: Historian and Author

The following biography of Mario Toglia was taken from the cover of his book, Preserving Our History.

Mario Toglia, son of Calitri born immigrants, Ernest Toglia and Giuseppina Codella Toglia, grew up in Brooklyn and attended local Catholic schools and Fordham University School of Education. He taught Romance languages in the New York City school system for thirty three years. Researching his family history was an avocation, done initially as a leisurely pastime, but the introduction of the “Age of Computer Technology” opened up new ways to search and study. The collection of data expanded outward after he connected with fellow Calitrani descendants. Mario Toglia acknowledges the ties that bind the Calitrani American community. “With all the material that I gathered,” he said, “it became obvious it was my generation’s mission to honor and preserve the immigrant history and legacy of Calitri.” The end product was his first book, They Came by Ship: The Stories of the Calitrani Immigrants in America. Mr. Toglia is a member of the Calitri American Cultural Group, the Italian American Studies Association and the Italian Genealogical Group. He currently lives on Long Island.

Book: They Came by Ship

This following overview was taken from the cover of They Came by Ship.

They Came by Ship: The Stories of the Calitrani Immigrants in America is the product of the Internet Age which brought together people researching their roots to their ancestral town of Calitri in Southern Italy. They came to know one another and, in many cases, rekindled old friendships and discovered distant relatives in second and third cousins. They began sharing stories on the Internet of the good old days, recalling neighborhoods where their parents and grandparents had settled after emigrating from Italy. These communities included Brooklyn, New Rochelle, Tarrytown, Dobbs Ferry, Batavia, Mount Vernon in New York; Montclair, Paterson, Newark in New Jersey; Stamford, Bridgeport, Torrington in Connecticut; Dunmore in Pennsylvania; Washington DC; and Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Their recollections proved to be so interesting and poignant to all that they needed to be set down in permanent form and preserved for future generations.

Book Copyright 2007 by Mario Toglia

Book: Preserving Our History

The following overview was taken from the cover of Preserving Our History

Preserving Our History takes a serious look into the history of the immigrants from the town of Calitri, Italy. These immigrants brought with them a strong sense of community and kinship. This helped ease their transition into America as they spread out to various locations and maintained their ties to fellow Calitrani as well as to their common values of family, faith, courage and mutual support. While gradually assimilating into their new environs, newcomers left paper trails of documents and information, some fortunately still treasured and preserved by descendants, many others stored in various archival institutes waiting to be discovered and added to known facts.

Book Copyright 2013 By Mario Toglia

Book: Celebrating the Heritage

The following overview was taken from the cover of Celebrating the Heritage

Heritage is something that is passed down from one generation to the next. It could be as real as photographs, heirloom objects, documents and a variety of paper souvenirs; or it can be as abstract as traditions, rituals, family lore and biographies. In Celebrating the Heritage, the Calitrani American kinship relishes its unique culture with a diversity of immigrant stories and recollections, including remembrances of trips to the familial hometown as well as its approaches to remaining linked to its legacy. Those readers or family history narrators, who seek perspectives on their own families, are likely to appreciate the experiences of this singular Italian American community in keeping its heritage alive in the present and preserving its history for the future.

Book Copyright 2015 by Mario Toglia

Ellis Island History

Ellis Island, located in the New York City Harbor, processed over twelve million immigrants from 1892 to 1952. In 1907 there were 1, 004, 756 immigrants processed. Overall, about two percent of those processed were not allowed to enter the United States. It is estimated that about forty percent of all Americans can trace their ancestry to someone who came through Ellis Island.

The following narrative about Ellis Island was taken from Wikipedia with minimal editing changes. It consists of an historical insight into the evolution of Ellis Island. It has three sections: First Immigration Station. Second Immigration Station, Early Expansions.

First Immigration Station

Anti-immigrant cartoon expressing opposition to the construction of Ellis Island (Judge, March 22, 1890).

The Army had unsuccessfully attempted to use Ellis Island “for the convalescence for immigrants” as early as 1847.Across New York Harbor, Castle Clinton had been used as an immigration station since 1855, processing more than eight million immigrants during that time. The individual states had their own varying immigration laws until 1875, but the federal government regarded Castle Clinton as having “varied charges of mismanagement, abuse of immigrants, and evasion of the laws”, and as such, wanted it to be completely replaced.

The federal government assumed control of immigration in early 1890 and commissioned a study to determine the best place for the new immigration station in New York Harbor. Among members of the United States Congress, there were disputes about whether to build the station on Ellis, Governors, or Liberty Islands. Initially, Liberty Island was selected as the site for the immigration station,[90] but due to opposition for immigration stations on both Liberty and Governors Islands, the committee eventually decided to build the station on Ellis Island.[e][92] Since Castle Clinton’s lease was about to expire, Congress approved a bill to build an immigration station on Ellis Island.

On April 11, 1890, the federal government ordered the magazine at Ellis Island be torn down to make way for the U.S.’s first federal immigration station at the site. The Department of the Treasury, which was in charge of constructing federal buildings in the U.S., officially took control of the island that May 24.Congress initially allotted $75,000 to construct the station and later doubled that appropriation. While the building was under construction, the Barge Office at the Battery was used for immigrant processing. During construction, most of the old Battery Gibson buildings were demolished, and Ellis Island’s land size was almost doubled to 6 acres

The main structure was a two-story structure of Georgia Pine, which was described in Harper’s Weekly as “a latter-day watering place hotel” measuring 400 by 150 feet (122 by 46 m). Its outbuildings included a hospital, detention building, laundry building, and utility plant that were all made of wood. Some of the former stone magazine structures were reused for utilities and offices. Additionally, a ferry slip with breakwater was built to the south of Ellis Island. Following further expansion, the island measured 11 acres (4.5 ha) by the end of 1892.

The station opened on January 1, 1892, and its first immigrant was Annie Moore, a 17-year-old girl from Cork, Ireland, who was traveling with her two brothers to meet their parents in the U.S. On the first day, almost 700 immigrants passed over the docks.[91] Over the next year, over 400,000 immigrants were processed at the station. The processing procedure included a series of medical and mental inspection lines, and through this process, some 1% of potential immigrants were deported. Additional building improvements took place throughout the mid-1890s, and Ellis Island was expanded to 14 acres (5.7 ha) by 1896. The last improvements, which entailed the installation of underwater telephone and telegraph cables to Governors Island, were completed in early June 1897. On June 15, 1897, the wooden structures on Ellis Island were razed in a fire of unknown origin. While there were no casualties, the wooden buildings had completely burned down after two hours, and all immigration records from 1855 had been destroyed. Over five years of operation, the station had processed 1.5 million immigrants.

Second immigration station

Design and construction

Following the fire, passenger arrivals were again processed at the Barge Office, which was soon unable to handle the large volume of immigrants. Within three days of the fire, the federal government made plans to build a new, fireproof immigration station. Legislation to rebuild the station was approved on June 30, 1897,[110] and appropriations were made in mid-July. By September, the Treasury’s Supervising Architect, James Knox Taylor, opened an architecture competition to rebuild the immigration station. The competition was the second to be conducted under the Tarsney Act of 1893, which had permitted private architects to design federal buildings, rather than government architects in the Supervising Architect’s office. The contest rules specified that a “main building with annexes” and a “hospital building”, both made of fireproof materials, should be part of each nomination.[112] Furthermore, the buildings had to be able to host a daily average of 1,000 and maximum of 4,000 immigrants.

Several prominent architectural firms filed proposals, and by December, it was announced that Edward Lippincott Tilton and William A. Boring had won the competition. Tilton and Boring’s plan called for four new structures: a main building in the French Renaissance style, as well as the kitchen/laundry building, powerhouse, and the main hospital building. The plan also included the creation of a new island called island 2, upon which the hospital would be built, south of the existing island (now Ellis Island’s north side). A construction contract was awarded to the R. H. Hood Company in August 1898, with the expectation that construction would be completed within a year, but the project encountered delays because of various obstacles and disagreements between the federal government and the Hood Company. A separate contract to build the 3.33-acre (1.35 ha) island 2 had to be approved by the War Department because it was in New Jersey’s waters; that contract was completed in December 1898.[123] The construction costs ultimately totaled $1.5 million.

Early Expansions

The new immigration station opened on December 17, 1900, without ceremony. On that day, 2,251 immigrants were processed.. Almost immediately, additional projects commenced to improve the main structure, including an entrance canopy, baggage conveyor, and railroad ticket office. The kitchen/laundry and powerhouse started construction in May 1900 and were completed by the end of 1901. A ferry house was also built between islands 1 and 2 c. 1901.] The hospital, originally slated to be opened in 1899, was not completed until November 1901, mainly due to various funding delays and construction disputes.] The facilities proved barely able to handle the flood of immigrants that arrived, and as early as 1903, immigrants had to remain in their transatlantic boats for several days due to inspection backlogs. Several wooden buildings were erected by 1903, including waiting rooms and a 700-bed barracks, and by 1904, over a million dollars’ worth of improvements were proposed The hospital was expanded from 125 to 250 beds in February 1907, and a new psychopathic ward debuted in November of the same year. Also constructed was an administration building adjacent to the hospital.

Immigration commissioner William Williams made substantial changes to Ellis Island’s operations, and during his tenure from 1902–1905 and 1909–1913, Ellis Island processed its peak number of immigrants.[129] Williams also made changes to the island’s appearance, adding plants and grading paths upon the once-barren landscape of Ellis Island. Under Williams’s supervision, a 4.75-acre (1.92 ha) third island was built to accommodate a proposed contagious-diseases ward, separated from existing facilities by 200 feet (61 m) of water. Island 3, as it was called, was located to the south of island 2 and separated from that island by a now-infilled ferry basin. The government bought the underwater area for island 3 from New Jersey in 1904, and a contract was awarded in April 1905. The islands were all connected via a crib walk on their western sides (later covered with wood canopy), giving Ellis Island an overall “E”-shape.[ Upon the completion of island 3 in 1906, Ellis Island covered 20.25 acres (8.19 ha). A baggage and dormitory building were completed c. 1908–1909, and the main hospital was expanded in 1909. Alterations were made to the registry building and dormitories as well, but even this was insufficient to accommodate the high volume of immigrants. In 1911, Williams alleged that Congress had allocated too little for improvements to Ellis Island, even though the improvement budget that year was $868,000.

Additional improvements and routine maintenance work were completed in the early 1910s. A greenhouse was built in 1910, and the contagious-diseases ward on island 3 opened the following June. In addition, the incinerator was replaced in 1911, and a recreation center operated by the American Red Cross was also built on island 2 by 1915. These facilities generally followed the design set by Tilton and Boring. When the Black Tom explosion occurred on Black Tom Island in 1916, the complex suffered moderate damage; though all immigrants were evacuated safely, the main building’s roof collapsed, and windows were broken. The main building’s roof was replaced with a Guastavino-tiled arched ceiling by 1918. The immigration station was temporarily closed during World War I in 1917–1919, during which the facilities were used as a jail for suspected enemy combatants, and later as a treatment center for wounded American soldiers. Immigration inspections were conducted aboard ships or at docks. During the war, immigration processing at Ellis Island declined by 97%, from 878,000 immigrants per year in 1914 to 26,000 per year in 1919.

Ellis Island’s immigration station was reopened in 1920, and processing had rebounded to 560,000 immigrants per year by 1921. There were still ample complaints about the inadequate condition of Ellis Island’s facilities. However, despite a request for $5.6 million in appropriations in 1921, aid was slow to materialize, and initial improvement work was restricted to smaller projects such as the infilling of the basin between islands 2 and 3. Other improvements included rearranging features such as staircases to improve pedestrian flow. These projects were supported by president Calvin Coolidge, who in 1924 requested that Congress approve $300,000 in appropriations for the island.