Personal Perspectives provides an opportunity for those who are part of the Nannariello and Passarella ancestry and other related families, whether family or friends, to provide personal first person accounts. Personal Perspectives is a way to facilitate enhancing this Ancestry story by providing anecdotal and oral history and ancestral reflections.

As mentioned in this story, Mario Toglia has contributed to Calitrani ancestry through his three books and his determined effort over many years. In each of his books, he uses the very effective memoir technique of having participants tell brief stories of their ancestors that provide fabric and insights and context into the immigration and their lives in Italy and the United States. Collectively Personal Perspectives add some fabric and context to the entire Ancestry story to assist in understanding and knowing these extraordinary people.

Personal Perspectives are intended to enhance the ancestry in a very personal and visceral way to get first-hand accounts and oral history.

Hopefully, this section will be enhanced by many others as a way of introducing additional personal insights and perspectives for the people we celebrate in this Ancestry. There is “contact” information in this Ancestry to permit contacting the Ancestry group and provide information that can be fashioned for these Personal Perspectives.

Heroes Luigi and Francesca Nannariello

By Steve Nannariello

I am Steve Nannariello, the grandson of Canio Nannariello. Following are my observations about Luigi and Francesca Nannariello, who are the parents of my Grandfather, and are my Great Grandparents. They became unknown to me when I began Ancestry research, that is now part of this Ancestry of six Calitrani Nannariello siblings who immigrated to the United States. The six Nannariello’s never saw their parents again, with the exception of Leonard Nannariello returning for a brief visit in 1931.

After many months of doing research on my Nannariello ancestors, it is my conclusion that my great grandparents, Luigi Nannariello and Maria Francesca Nannariello, made heroic efforts to make possible that six of their siblings immigrated to the United States to find a new life and new opportunities. They are my heroes. I only know them to the extent that ancestry research and some limited oral history. My grandfather, Canio Nannariello, and his other five Nannariello siblings, endured many obstacles on their journey to leave Calitri and immigrate to America and to make a new life. My focus began to be centered on Luigi and Francesca, the parents that were left behind.

Donato Nannariello, brother of Luigi Nannariello, immigrated to the United States and specifically to White Plains, New York in 1894 with his wife Vincenza TogliaNannariello. They purchased an apartment house in White Plains at 21 Main Street that was both their home and a hotel. Also, this home became the portal for the six children of Luigi Nannariello. Donato and Vincenza sponsored and provided boarding for many Calitrani and all of the six Nannariello siblings at 21 Main Street.

We can assume that Donato found jobs for them probably in the restaurant and bar and related businesses. My grandfather Canio and his siblings must have had a comfort zone coming to the United States knowing they had this family support system in place. Luigi and Francesca made this possible by encouraging and endorsing their children to leave for the opportunity for a better life. Among the ten siblings of Luigi Nannariello and the eleven siblings of Francesca Martiniello Nannariello, only their family provided and opportunity for all of their children to immigrate to the United States.

In 1921, my grandfather Canio was the next to the last sibling to immigrate to the United States and at that point there were more of Luigi Nannariello’s children living in the United States than in Calitri. The immigration was completed in 1924, when Rosa Nannariello DeCosmo, who married Giuseppe DeCosmo in Calitri, immigrated to New Rochelle, New York. Finally, Luigi and Francesca had given all of their children to a new country and new opportunities.

Oral history indicates that the Nannariello siblings in the United States all supported the idea that Leonardo would return to Calitri and try to persuade their parents to immigrate to the United States and join their children. The oral history is that Leonard was not able to change their mind and returned home after a rather short visit. He was the last of the children to see Luigi and Francesca. Luigi died in 1931, shortly after his son Leonard returned for a visit. Francesca died in 1935. Both never saw their children again after their departure years earlier.

Luigi and Maria would never meet or hold any of the many grandchildren that were born and raised in the United States. They would never meet their children’s spouses and participate in their weddings and their family events. They would spend the last years of their lives never to celebrate a birthday or a holiday with their children or grandchildren. When Luigi died 1931 and Francesca died in 1935, there would be no child to participate at the end of their lives for the funeral service. Though this is the story of one Nannariello family from Calitri, it is a universal story that millions of emigrants from Italy and throughout Europe could share. They were all Heroes for the sacrifice to encourage and facilitate their children finding a new life in a new country.

We must reflect on the millions of Italians and Europeans from various countries, that participated in the Great Immigration of the late Nineteenth Century and the early decades of the Twentieth Century. God Bless Luigi and Francesca Nannariello and all the Mothers and Fathers who made the ultimate sacrifice. They were Heroes!

Angie Nannariello’s Pearls

By Lynn Nannariello and Richard Nannariello

I am Richard, the youngest son of Angie Nannariello and Charlie Nannariello. I am five years junior to my older brother Louis Nannariello, who born in 1928. This is a story of a happenstance legacy that started back in the 1950’s and came to fruition in 2019 when my niece, Lynn Nannariello, and I had stumbled on a conversation that uncovered some interesting past.

In early 1953 and for the next 18 months, I was stationed with the U.S. Army in South Korea. I completed the tour along with hundreds of thousands of American service members who had remained in Korea after the war ended on July 27, 1953. During the tour in Korea, soldiers were given a leave—known as R and R or Rest and Recreation—to go to Tokyo or Hong Kong for a week. R and R was granted about every six months and most soldiers took advantage of this opportunity. In early 1954, I was one of about two hundred soldiers, flown out of K47 Air Force airbase in Chunchon, South Korea on a Globemaster troop transport plane and arrived at the Tachikawa Air Force airbase in Tokyo.

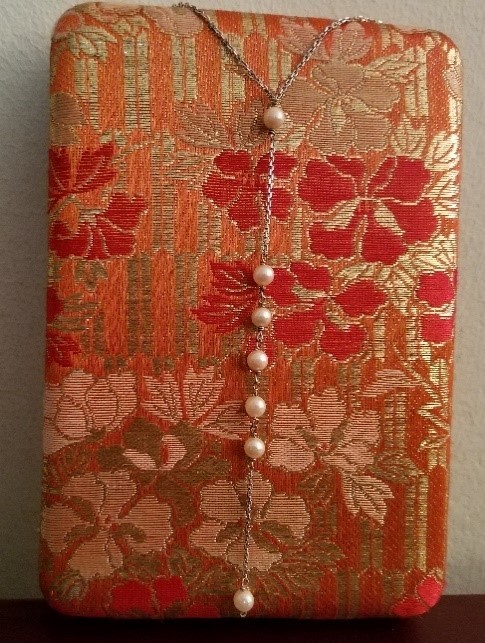

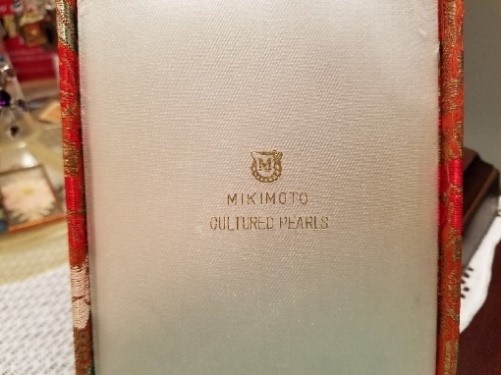

In 1953, Tokyo displayed none of the ravages of World War II, which had ended a short eight years before. The city was clean and crowded and vibrant, and full of wonderful restaurants and endless entertainment. For a nineteen year old, Tokyo provided a great opportunity for exploration. Also, Tokyo was a shopper’s paradise. I went to the Ginza, the city’s major shopping area, to find a gift to send to my mother, Angie Nannariello, in White Plains, New York. The Ginza was a kaleidoscope of shops, massive numbers of people, restaurants and neon signs, where seemingly anything you could imagine was available for purchase. There appeared to be a Mikimoto store on every block. Mikimoto at that time, as now, is considered the epitome of retailing the finest cultured pearls in a limitless variety of designs. I bought my Mother a necklace containing ninety two cultured pearls and a matching pair of pearl earrings at one of the Mikimoto stores. I shipped the gift to my Mother and remember her expressing her appreciation by way of a letter. Also, I recall discussing the pearls with my Mother after returning from South Korea a year or so later, and she was again appreciative. I don’t recall discussing the pearl jewelry with her again.

Angie Nannariello died in January 1996 and her granddaughter and her first grandchild, Lynn Nannariello, inherited the pearl necklace and earrings. Lynn kept the pearls tucked away in the original Mikimoto case for many years and until she eventually found an extraordinary use for them. Lynn did not know the source of the pearl necklace and earrings. It wasn’t until December 25, 2019, Lynn and I linked the story of the source of the pearls and her efforts to pass on the pearls to Angie’s grandchildren. Through providential circumstances and Lynn’s efforts Angie’s pearls became part of a family tradition.

In 2008, Stephanie Nannariello, Lynn’s niece and Angie Nannariello’s great granddaughter was turning sixteen, a significant birthday. It occurred to Lynn that since she did not wear her grandmother’s necklace, the pearls could be put to better use in making a piece of jewelry for Stephanie. She took the pearl necklace to a jeweler and together they designed a bracelet employing 24 of the pearls alternating with gold beads. Stephanie received the bracelet for her 16th birthday. Lynn liked the idea that Stephanie now owned a bracelet created from the pearls of a necklace that had belonged to her grandmother and Stephanie’s great grandmother. In 2013, when Stephanie turned 21, Lynn gave her a pendant made of alternating gold beads and five of the pearls from her grandmother’s necklace.

Lynn decided to continue this idea with her younger niece and another of Angie Nannariello’s great granddaughters, Kayla Nannariello, for whom she had two pendants made. One was a circle pendant that alternated nine of the pearls from the necklace with gold beads. The second piece was a sterling silver drop style necklace with a pearl at the top of the drop and six pearls in the drop. Lynn had the same drop style necklace made for Stephanie in December 2019. Since Stephanie and Kayla now each had the same drop style necklace made from Angie’s pearl necklace, Lynn thought it would be nice if they all had the same necklace, so she also had one made for herself in 2019.

On December 25, 2019, more than sixty five years after the purchase of the pearls in Tokyo, Lynn sent me an email explaining what she had done with the pearls she had for all these years. Again, Lynn did not know the source of the pearls bequeathed to her by her Grandmother. I had not given any thought to these pearls in all these years and did not know that Lynn had them. It took a while, after reading the email and admiring the pictures of the pearl jewelry to make the connection with the pearls long since out of my mind or memory. I called Lynn and asked her if she had the original box for the pearl jewelry and whether it was marked Mikimoto. She had the box and it was marked “Mikimoto” on the inside. Lynn sent a photo of the Mikimoto box and distant memoires confirmed that the pearls were those purchased in Tokyo in 1954.

Lynn has now extended the pearl legacy to yet another generation by having a fourth necklace made identical to those created for herself, Stephanie and Kayla. This necklace is made for Lynn’s great niece. Olivia Nannariello, who was born December 13, 2015 and is Angie Nannariello’s great great granddaughter. It will be given to Olivia by her parents at the appropriate time. Thanks to Lynn, four of Angie’s descendants share her legacy through the string of pearls that Angie kept all those years and gave to Lynn in 1996.

Remembrance of Angie Nannariello

By Richard Nannariello

Angie Nannariello was an extraordinary cook and in the Italian tradition cooked the food with excellent ingredients and slowly. She did extraordinary things with condiments, loved cooking and never wrote down a recipe. I have her recipe for pasta e fagioli that she gave provided after a long conversation on how it was cooked. No attempt to duplicate her recipe every achieved her perfection, but it is wonderful to be able to try.

Pasta fazoola is slang Italian

For the more correct pasta e fagioli

Literally pasta and beans

In this recipe that will be explored

All measurements are not specific

It is not a teaspoon of this or that

But the less precise and abstract definition

Of some of this but not too much of that

And certainly not too little of something else.

The olive oil is pungent and green and luminous

Like the color of a newborn frog

The single medium minced onion

Breathes and succors the olive oil

As they symbiotically savor each other

Canned diced tomatoes immersed in olive oil

Baptizing the now sautéed onions relentlessly

Joined by a can or two of cannelloni beans

All vibrantly and valiantly seasoned

With unmeasured basil and oregano and black pepper

And crunched bay leaves

Some unregulated dashes of salt and pepper and parsley

All permeating the air and delighting the nose

And tearing the eyes.

The Ditalini pasta

Is bunched into three or possibly four

Hand measured quantities

Farfalle or elbows pasta can be mixed or substituted for the Ditalini

Bathed in foamy boiling salted water

Soothed with olive oil

And at a precise though not timed moment

The pasta is delivered from the pot

And now swishes around in the colander

Delectably and delightfully al dente

Not allowed to stay a moment too long

And saving every drop of the drained water

The pasta splashes into the tomatoes and condiments

While the saved salty and olive oil enhanced water

Is incrementally added and not measured

And thereby turning the thick mass

Into a soupier consistency.

I never make pasta e fagioli

That Mom does not come to mind

Her patient commitment to the possibilities

Of a fine pasta e fagioli

Her good senses and lack of preciseness

In measuring ingredients

The joy of watching her across the table

Laughing with her head slightly held back

The strong features of her face

Defined by her prominent Roman nose

The arthritic hands that relentlessly and tirelessly

Choreographed a thousand dishes

As she breathed in the aroma

Of the pasta e fagioli

Her hands in a prayer like gesture.

Since she last made her pasta e fagioli

It has never tasted as good

Or smelled as aromatic

But I will continue to make it

As a way of saying a silent prayer

To the legacy of her gift and her mentoring

Her mystic mastery of the ancient process

But it shall always be less than perfect than her pasta e fagioli

And her enduring and perfect love.

Grace Nannariello Trotta Saturday at the Movies

By Richard Nannariello

This story was initially written years before this Ancestry project was conceived. Originally, there was no intention that the story would be anything more than a short memoir of a very pleasant childhood experience and memory. The memory is about me, Richard, as a nine-year-old nephew of his Aunt Grace Nannariello Trotta, one of Charlie Nannariello’s three sisters. Grace was born Grazia Nannariello and was the first of the six Nannariello siblings to leave Calitri, Italy and immigrate to the United States. I found out many years later that Aunt Grace came to the United States in 1907 when she was sixteen and by herself. She arrived in New York City; went through Ellis Island; and took the train from Grand Central Station in New York City to White Plains, New York. She was sponsored by and initially stayed with her Uncle Donato and Aunt Vicenza Nannariello. She slept her first night in the United States at 21 Main Street in White Plains the home of Donato and Vincenza.

There is a limited amount of ancestry history in this story and unfortunately there is not a lot about Aunt Grace’s life beyond the wonderful experience and gift she gave to her nephew. Memories of our Saturday mornings has opened many doors of my memory and of the place and time in the early 1940’s, which we can always allude to as being “the good old days.” Grace was in the United States many decades before this story occurred. She had a husband and four children. This story provides memories that are now revisited after more than seventy-five years have passed. In the telling of this story, I have forgotten some of the details and possibly a few memories are a little blurred through the lens of time. But they are pleasant memories and wonderful to recall. God Bless Aunt Grace for these memories.

Aunt Grace spoke with a lovely Italian accent that was slightly guttural, but soft and almost musical. She had lovely intelligent eyes that were colored somewhere between blue and hazel, she wore large black shoes tightly laced, and either a black dress or bright prints. She had that “Nannariello look” that anyone who knew the Nannariello family and seeing and hearing her, would immediately know that she and Charlie, my father, were brother and sister. Part of that look was in and around the eyes.

Aunt Grace was born Grazia Nannariello in 1891 in Calitri Italy. Just as her brothers and sisters would later, she arrived in the United States and adopted an Americanized version of her name, specifically Grace. Aunt Grace always seemed to be old from the view point of a nine-year-old around 1942. A I do the chronological arithmetic; she was a middle-aged woman of about fifty-two. Aunt Grace had a perpetual smile on her face, which lived on the crest of her eyes and glowed soft and warm. She never displayed any anger, except when she and my father argued, always in Italian, about something that could not have been serious, because it always ended in laughter and warm feelings.

The Great Depression was behind us and the Second World War had started for the United States in December 1941. Housing was sparse and there was no building of homes during the Second World War. My father and mother rented a house on Lester Place in the Battle Hill section of White Plains, New York. Aunt Grace and her daughter Lucy lived with us as part of our extended family. Aunt Grace and Lucy had one room they shared, they ate all their meals with us and they lived within all the bounds of the house and they were part of our lives and our family.

Aunt Grace had worked in restaurants as a cook in previous years and the reason for her leaving that work is not known. In 1942 she worked cleaning a movie theater in downtown White Plains, New York. It was the Loewe’s movie chain on Main Street about midway between the New York Central Railroad Station and Mamaroneck Avenue, another shopping street that competed with Main Street. She walked back and forth from Lester Place starting about 6 :30 AM each morning to the Loew’s movie house. My father had already departed to drive to Scarsdale where he worked at the Scarsdale Diner as a short order cook, which was his occupation for over fifty years.

However, Aunt Grace would take me with her on Saturday’s and the expectation of this opportunity delighted me all week. Walking to the Loew’s on downtown Main Street, began with a pleasant walk down Chatterton Parkway. This was a long meandering street with trees parading down one side and with large homes built on the side of a hill. The tree side was a deep wooded area that ran down to the Bronx River Parkway, which at that time was the first parkways in the United States. At the bottom of the hill was Central Avenue and Main Street and the New York Central Railroad Station, a magnificent station for its time and . It was completed in 1915, with a new elevated track that spanned Main Street, which originally had been Railroad Avenue.

The walk continued for several blocks up Main Street until we could see the Loew’s marque in the distance when we were a few blocks way. It was exciting to see the names of the movies on the marquee and the posters along the lobby wall with the names of the actors and some definitive photos from recent movies. On Saturday’s mornings, a very short man on a very tall ladder would place the names on the marquee of the movies with black plastic letters sorted in an array of boxes spread across the sidewalk. Beneath the movie titles were the starting times of the movies.

On Main Street there were no traffic lights; Policeman wore jackets with collars pushing up their neck even on the hottest of summer days; there were no parking meters; and parking was on both sides of the streets. Stores stood side by side with large signs promoting their names and sale signs glued to windows or hand written on white washed windows touting the latest sale. The store windows enticingly displayed wonderful items, so one could really shop from the sidewalk. There was the latest Tom McCann shoes store; Woolworth’s Five and Ten Cents Store with endless bargain offers; the Italian butcher with meat hanging among the twisted strips of flypaper hanging from the ceiling; the German bakery with strudels and cheesecakes. There were stores like Genung’s department store, where the “rich people” shopped and displaying the latest seasonal fashions from New York City. It was a kaleidoscope of everything the world had to offer. And Aunt Grace and I would walk it every Saturday and see this panorama of life displayed before us.

Aunt Grace would on occasion start talking Italian and not understanding, I would listen intently because it sounded pleasant and musical and very mysterious. She would realize what she was doing and laugh heartily and refer to herself as being “pazza” which I learned meant “crazy.” I always imagined how wonderful it would be to speak Italian and I would sometimes invent Italian gibberish, pretending to speak Italian to her, and she would laugh vigorously. I would basically use English words and add a vowel to the end of the words, making it sound kind of Italian. When I saw a movie in which the actors had to speak with an Italian accent, my practiced ear knew that it was a poor effort if it did not sound like Aunt Grace’s accent. Sometimes she used an Italian word, like “andiamo” or “let’s go”; or “aspetta” or “wait; or “lentamente” or “slowly.” She would promise to teach me to speak Italian, which I thought may be a problem. My parents, Charlie and Angie Nannariello, sometimes spoke Italian when they didn’t want me to understand or know about something that a little boy should not be aware of. Sometimes I would say the Italian words Aunt Grace taught me such as “grazie.” She would show her pleasure and rub her hand through my unkempt hair.

We would enter through the Loewe’s lobby which was lined with glass cased movie posters showing action photos or intimate love scenes with Betty Davis and Joan Crawford or Humphrey Bogart or Spencer Tracy. I would have been glad to read every one of those posters, but there was no time, and we would proceed to what Aunt Grace referred to as the backroom. The room was filled with mops, brooms, ladders, towels, large buckets, and it always had the pungent odor of ammonia. As we arrived, so did Dorothy, a thin black woman, with a soft voice, a toothy smile, and beautiful long hands. She always called me “darlin” and would give me a warm hug. I could tell that she and my aunt really liked each other. They would greet each other by reaching out and touching cheeks, just like Aunt Grace did anytime someone came to our house. There was no talk about what to do. They each would put a smock over their dress, change their shoes, and exchange small talk. Aunt Grace and I went to the downstairs of the theater and Dorothy headed up to the balcony, and they exchanged warm goodbyes as if they were permanently parting.

Aunt Grace proceeded to the bathroom, with me in hand and unlocking a closet with its large and heavy door. She pulled out a large wash bucket, filled it with hot soapy water, picked up a mop with long rope-like threads, putting the mop in the water and dragging it across the floor. Once she let me try doing this because I offered to help and thinking I could ease her burden. She laughed as I desperately tried to move the wet mop across the white tiled floor, until my arms ached and beads of sweat filled my forehead. She gave me a warm hug for my efforts and said someday I would be able to help her with the mopping. I wondered how she could move that heavy wet mop.

I knew the routine of staying with her for a short while until she handed me a feather duster, with large gray feathers and a handle about half the length of my body. I would proceed into the softly lit theater, with the large silent white screen looking down from the stage and a large light sitting on top of a very high lamp stand. There were thirty-nine rows of seats identified with gold letters on the first arm of each row, from A to Z, and then again from AA to MM. The theater had a middle section and smaller left and right sections separated by aisles. I proceeded to the first aisle, looking up to the stage and large screen towering over me. I sometimes wondered how I would survive if the screen fell on me. I proceeded to snap the chair seat back for each seat that was not already snapped back. Then I would dust the armrest of every seat with the large feather duster. I wondered how the arm rests got dusty with all of the people trafficking through the movie house seven days a week. Aunt Grace explained, we had to make sure they were clean, and each and every one had to be feather dusted. I never skipped or missed on armrest, even though in the softly lit and half dark theater no one would have noticed. But it wouldn’t be fair to Aunt Grace if I cheated. That was one of the many lessons learned, about doing what you are told to do and do it right the first time and on time.

By the time all of the seats had been pushed back and the arm rests feather dusted, my arms were aching and I was more than a little tired. Aunt Grace would be done with the men’s and women’s bathrooms, always looking tired, and would proceed to the first aisle with a garbage pail, a small broom, and a dustpan with a long handle. Now was the hard work of sweeping the floor of every section, left side and right side and middle. There was candy, popcorn, gum, paper wrappers, newspapers, and sometimes unpleasant things. Aunt Grace would bend down and standup, it seemed a thousand times. She would sometimes fill up the garbage pail and have to get a second one. I would trail along and pick-up items as fast as possible, but Aunt Grace moved more quickly and I thought with a little pain from all of the bending.

She would also find coins on the floor: pennies, nickels and dimes and occasionally a quarter. She would drop the coins into the large pockets in her smock. It was wonderful to hear the jingle of the coins. At the end of the morning, we would spread the coins on a table and she would give me a handful of those coins from her apron. I quickly counted the coins and it was usually around fifty cents. An amazing amount of money and the sound of the coins jingling was so pleasant. Among the clutter around the chairs, we would sometimes find handkerchiefs. There were more handkerchiefs if there was a real sob-story movie with Betty Davis or Joan Crawford or Barbara Stanwick or Olivia De Havilland.

At about ten thirty, Aunt Grace and Dorothy would stop and sit in the lobby in two large chairs, separated by a table and a large art deco lamp. I would sit on a foot stool we got from the storage room. They would talk about what parts of their body ached that particular day. They would have something good to say about President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, never using the ubiquitous initials of FDR, but always President Roosevelt or Mr. Roosevelt. Dorothy shared her worries about her son who was a cook in the Navy on some ship, but she had no idea where. Aunt Grace talked about some of her many nephews in the military and mentioned strange named places in the Pacific and Europe where they were. They both wondered when the war would end. A few times they talked about World War One and I was amazed that the wars had to be numbered. I wondered who had the job of assigning the numbers to the wars, and hoped there never would be a war with the number three.

They would share a cup of coffee and give me a cup with half coffee, half milk and three teaspoons of sugar. We would eat the buns from the German bakery, where Dorothy had stopped on the way to work. They always asked me about my school work and I shared the latest challenges of multiplication tables. I displayed my capabilities to do eight times eight, nine times nine, and ten times ten and other variations on multiplication. They were both sincerely impressed and encouraged me to learn those multiplication tables so I wouldn’t be cleaning movie houses early in the morning when I grew up. Aunt Grace would share half of a sandwich with prosciutto and provolone cheese and Dorothy would share a cup of beans and a sweet cake. It was always a pleasant mystery what surprises would come with the sharing of food.

Then back to work. The work would continue until about noon, and everything had to be completed because tickets would be sold starting about twelve thirty. If one or both of the movies were really good, there would be people waiting outside to buy tickets. In the summer warm days, the air conditioning would come on about ten o’clock so the movie would be already cool for the moviegoers. The air conditioning would flow out of the lobby to the sidewalk under the marque. Sometimes people would stand in front of the movie on the sidewalk to enjoy the air conditioning. I think the only places that had air conditioning were the movies. There was an RKO Keith’s farther up Main Street, but I had never been to that movie before. Somebody once told me that some people had air conditioning in their homes, but at the time I really didn’t believe that.

An hour or so before the ticket office would open in the lobby, the lady selling the tickets and the man who took the tickets and the ushers would show up. The Ticket Taker wore a blue and yellow uniform and a hat, and looked as dressed up as some of the characters in the movies who were generals in some of the stories. There were two Ticket Takers that would work on different Saturdays. One of the Ticket Takers wore a uniform that was too big for him and he could kind of turn his body around inside the uniform while the uniform stood still. The other ticket taker wore a uniform that was too small for him and he looked very uncomfortable and he could hardly move because of the constraint of the uniform. It took several Saturdays before I figured out, they were wearing the same uniform. The Ushers wore a uniform, but not as fancy as the Ticket Takers. And the Ushers had a flashlight to show the moviegoers to their seats if the movie had already started and the theater was dark, except for the small lights on the last seat of each row. When I was in the theater when it opened and before the movie started, there were some bright lights on and the theater looked so big. But when the movie started and the theater got dark, it was fun disappearing into the dark and feeling small and the movie screen would grow to look so big and it was “show time.”

Aunt Grace and Dorothy changed their clothes and they walked a little slower as they prepared to leave. They each gave me a big hug and then each other a hug. I would be able to sit in the theater as the very first movie goer for the day, with the pick of any seat in the house, and the coins in my pocket, and two pieces of candy that I bought in the lobby. I never imagined that life could ever be better and with more opportunity. As the movie was starting, Aunt Grace would be walking down Main Street and up the big hill on Chatterton Parkway. She would be glad to get her large black shoes off when she got home. My mother would be waiting for her and they would sit in the kitchen and drink coffee. Aunt Grace would take a nap while I was watching two feature movies, a newsreel, a cartoon, and the coming attractions, without even paying the twenty cents for admission. I liked the newsreel, but did not like the newsreel of Pearl Harbor which they showed it some time to remind us why we had to fight the war. At the time I didn’t know exactly where Pearl Harbor was, but I knew it was in Hawaii and that was far away.

I loved Saturday, except for getting up early. And I loved feather dusting the arm rests, and listening to Aunt Grace and Dorothy talk about the world, and seeing the movies after the work was done. I would walk through the lobby and look at all the posters and memorize the names of all the actors. I would walk up Main Street with the few coins jingling in my pocket and my head full of the magic of the double features. I didn’t know at the time how much I learned from Aunt Grace. I learned about patience, punctuality, the joy of doing the most menial job as well as you can, and respectfully listening to older people talk, and a lot of other things that just became part of my character and life. I learned that two women, Aunt Grace and Dorothy, from two cultures and two colors could have a warm friendship. I learned that a young boy could spend part of the day with his old aunt and never be bored and have a good time. I learned to enjoy the sweet sound of English spoken with a soft Italian accent, brought here from across the Atlantic Ocean from Italy. I knew I wanted to go to Italy one day. I learned to enjoy the lovely accented Southern drawl from Dorothy brought from somewhere in the Deep South by her parents or her grandparents. I learned that we are all different but shared the same humanity and opportunity to be kind and share a common humanity.

Through the years, every time I sit back in one of the multiplex movies with Dolby sound, a huge screen, and stadium seating, a huge lobby with wine and hotdogs and popcorn, I wonder if anyone took the trouble to feather dust the arm rests and sweep the floors and clean the bathrooms. And with the diligence of Aunt Grace and Dorothy.

Now this all happened in the 1940’s and that was many years ago. I am not certain if all of the details are absolutely correct, but it is the best I can recall. But this is not the time to play games or second guess yourself about a beautiful memory that may fade a little but will never tarnish. It was Saturday at the movies. The next day there would be the Sunday newspapers and the comics. And next Saturday Aunt Grace and I would make that trip down Chatterton Parkway to a very magical place.

When returning from Korea in early 1955, I had the occasion to go to the Loew’s movie theater for the first time in a few years. The memory of those Saturdays was as joyful as the day they were lived. A lot had changed. The people who had worked there were all gone, the theater seemed smaller, many of the movies were in color rather than black and white. I checked the arm rests and they seemed clean, but the floor was sticky and the bathroom was not as clean as when Aunt grace and Dorothy took care of them.

There was so much that had changed including the movies, the times, the theater, Aunt Grace and Dorothy not being there, and I had changed. But the memories are treasured and cherished and are such a wonderful gift by a loving Aunt to a young boy.

Aunt Grace died in 1960 at the age seventy. God Love her and thank her for Saturday at the Movies.

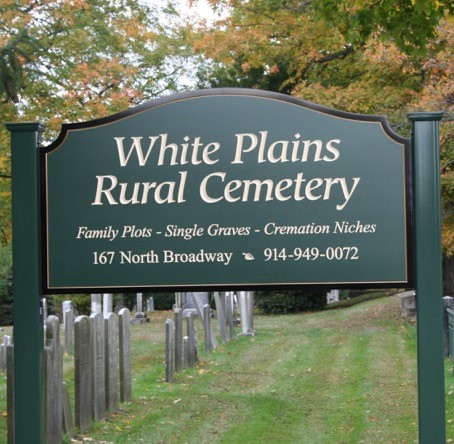

White Plains Rural Cemetery

By Richard Nannarello II

White Plains Rural Cemetery is a historic cemetery located in the city of White Plains, Westchester County, New York. The cemetery was organized in 1854 and designed in 1855. It contains miles of narrow, paved roads, none of which are in a straight line. The roads create circular and lozenge-shaped areas for burials. Also on the property is a former church that is now the cemetery office. The church was built in 1797 as the First Methodist Church in White Plains. It is a two and a half story building with a high-pitched gable roof. The church was modified for office use in 1881.The cemetery was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2003.

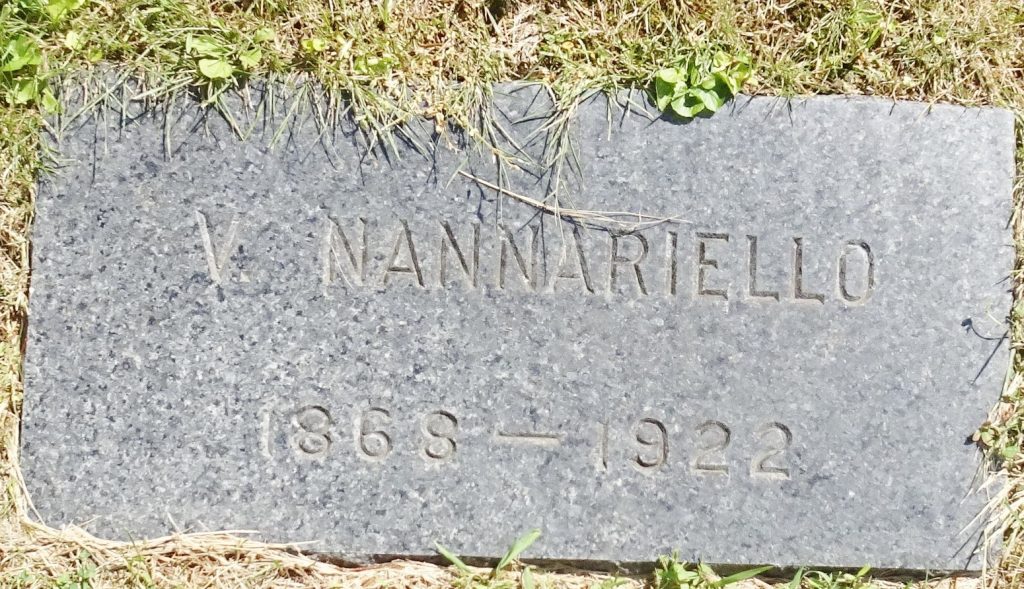

After exploring the cemetery, I just confirmed my hunch that the Cestone family is connected to the Nannariello family. B490Angelina Nannariello (1866 -1954) was the spouse of Vincenzo Nannariello (1868 -1922), who was my grandfather Charlie Nannariello’s uncle and possibly one of the first Nannariello to settle in White Plains.

It was a puzzle why both husband and wife are buried in the Cestone family plot. The 1940 census below reflects that Angelia Nannariello was a member of the Cestone household at the age of seventy three, and therefore was born in 1867. I assume that when Vincenzo passed in 1922, she eventually moved back in with her Cestone family. This is also why both family plots are adjacent by design because they were connected. Moreover, in the landscape picture below, the monuments of both family plots are connected by an arc of light. Perhaps a Divine message! Puzzle solved!

I drove to the White Plains Rural Cemetery on North Broadway to search for graves of the Nannariello family. Except for a worker, I was the only person in the Cemetery. It’s truly a wonderful peaceful place that’s nicely landscaped with narrow winding roads, natural beauty and much history. The office was closed, but I walked around listening to my music while searching for these graves. Given the size of the Cemetery, it was like looking for a needle in a haystack, so I didn’t expect much. However, I did note many historic graves with old Westchester names. As an example: Horton, Miller, Purdy, Griffin, Buckout, Ferris. These are names that can be found around White Plains and appear on streets and buildings and historic places. There are even graves of soldiers from the Revolutionary War.

After an hour, I came across a monument for the Cestone family. I recalled this being a Calitrano name. This beautiful monument had a large cross on top, and I admired it. As I turned away, I stumbled upon a foot stone, and I was compelled to read it:” V. Nannariello 1868- 1922″. What a discovery by chance! This was the grave of Vincenzo , the first Nannariello to emigrate to White Plains, and Grandpa Nannariello’s uncle. To the right of his grave is the foot stone for the grave of “A Nannariello 1866 – 1954.” I assume this was Vincenzo’s wife and Grandpa Nannariello’s Aunt. Perhaps she was born a “Cestone” and therefore the reason why both these graves were commingled with the Cestone family plot.

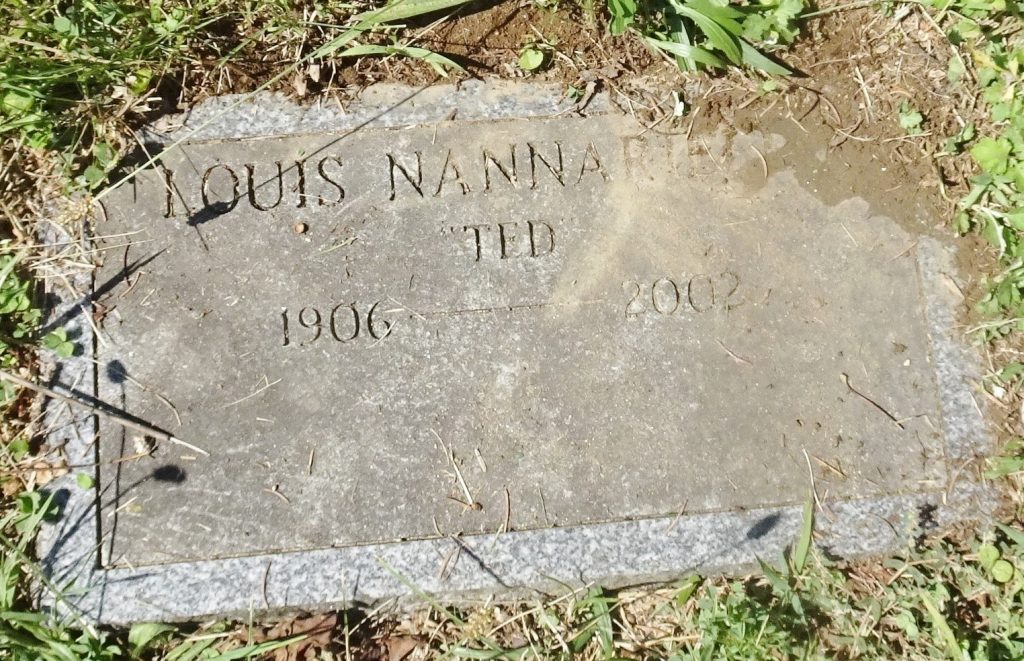

Directly across this narrow road from the Cestone family plot, I found the Nannariello family plot and only by chance! The centerpiece is a beautiful tall monument with a statue of Christ on top. In this family plot I noted the graves for Donato, Vincenza, Michael, Lawrence, and Louis “Ted” Nannariello. Commingled in the Nannariello family plot are the graves for Michael and Marie Toglia. Again, all Calitrani names. Besides being related, it’s obvious that the Nannariello’s, Cestone’s and Toglio’s were all very close in their lifetimes and explains their being buried together.

These family plots can easily be found near the North Broadway entrance to the Cemetery. After entering through that entrance, make a first right, turn a short distance, and then your first left turns down a narrow road. The plots are about twenty five feet down this road on both sides.

I walked around and noted other family plots of Italian origin, such as Codella, Rutigliano, Stanco, Savanella, Taglione. For some reason, the Italians favored the north eastern side of the Cemetery.

Looking Easterly, the Nannariello family plot is on the left side of the road. Note the tall monument with Christ on top. The Cestone family plot is on the right side of the road and note the large monument with the large cross on top. These monuments are facing each other. One must wonder if this was done by design. There is the monument for the Nannariello family plot. It is very beautiful.

Looking Westerly, the Nannariello family plot is on the right side of the road and again the tall monument with Christ on top. The Cestone family plot is on the left side of the road and note the large monument with the large cross on top. It’s late in the afternoon and the sun is low. Note the sun beams coming downwards from the sky and the arc of light connecting the Cestone monument to the Nannariello monument. Amazingly beautiful! Perhaps God is giving a message.

The obvious connections are that if not all of the people, certainly some of the people in that cemetery are in the Ancestry story of the many who have parted from Italy. The connection is that many ended up in White Plains and eventually in this cemetery. The extraordinary monuments and the grouping of many Calitrani in one cemetery in one area is a great story of the immigration and the worthy Emigrants who decided to live and die in the White Plains area and leave a legacy of their ancestry that still carry their names.

White Plains Rural Cemetery Photos

By Richard Nannariello

The White Plains Rural Cemetery in White Plains, New York, is the final resting place for many Calitrani who chose White Plains and other parts of Westchester County to live their lives. Following are some of the marking stones and statuary for some of the Nannariello and Cestone families that occupy an area of the cemetery.

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

Lawrence Nannariello 1896-1977

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

Marie Toglio 1854-1947

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

Son of Donato and Vincenzo Nannariello

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

The Patriarch and Matriarch of the Family of 11 Children who lived in White Plains at 21 Main Street and became Sponsors of Luigi and Francesca Nannariello’s six children who immigrated to the United States.

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York

White Plains Rural Cemetery, White Plains, New York.

Nannariello Family Art

By Alfonso Nannariello

He was a Calitrani, poet, author of about 16 books, teacher, historian for the Nannariello Family.

Following is an extensive and scholarly research of the Nannariello heritage in the arts completed by Alfonso Nannariello, who lived in Calitri. Alfonso has researched various Nannariello’s and relatives, not all sharing the same last name, who were involved in the arts over the past centuries. The accomplishments of these artists are very impressive.

We are grateful to Alfonso Nannariello for permitting the use of this research in this Ancestry effort. He has made other contributions to the Website and has been very helpful in the research effort. Grazie Alfonso who unfortunately during the development of this Ancestry passed away after a brief illness and hospitalization.

This informative article was translated from Italian by software translation without any further editing after the translation. There will be some translation issues, but it will not prevent understanding the text and appreciating this historical perspective.

The Family Art

It is perhaps no coincidence that, sometimes, the characters of the crib were made (some freehand, others double matrix) by my father (Leonardo, class 1913), who had learned from his father (Alfonso, class 1879), who had taught him, in addition to his craft (the bricklayer), to paint scenes and figures on the wall, to make masks for the carnival and papier-mache masks for the papier-mache, high-rise plaster and all-round sculptures with a casting. My grandfather Alfonso had learned all these things from his father (Joseph, class of 1856), who had learned them from his father (Lorenzo class 1829). Lorenzo, however, had learned the things he could do on his own. In fact, since Vincenzo, his father, on June 7, 1826 had married [Maria] Francesca Lampariello of Vito (who had a license for fabricar vases of clay and another of faenzaro) and Gaetana Di Napoli, Lorenzo as a child was able to attend the family furnace, and there, like all children who ask for clay to the baker, he must have started to make various puppets, until he became capable of that art then passed on to his.

For ancient use of family, my father painted. On the front of the arch under which heacqui, he had depicted the Escape to Egypt, and a wolf’s head on the wall at the head of his bed. For ancient family use, my father had learned from his father. From him he had also learned to make masks for the carnival, made from a prototype of clay, and Cristi crucifixes of papier-mache, as well as, at the collage, plaster sculptures with several high-rise and all-round undercuts. In his family there were painters and ceramicists. Almost certainly these made figures copied somewhere or inspired by the truth. The copy, while facilitating their execution, compared to the thing reproduced, must have measured their ability, stimulating them to do better or to make them proud.

By Vincenzo Nannariello in the attic of the house I found an oil portrait made on a glass plate. The half-bust was enclosed in a small oval under which was his name written with black and threaded with gold. It was supposed to be a self-portrait done before he left. He had left it in the house, perhaps so as not to be forgotten. Of him, from a book on The Archconfraternity of the Immaculate Conception of Calitri, I learned that between 1910 and 1914 he resided in New Rochelle where, among other things, he painted. His image of the statue of our Madonna for the church of the Calitrani of that city; his other works, I know from that article, which gave them away.

In acts of more than a hundred years before I was born, written by Giovanni Stanco and Luigi Cerrata, there is a Michele Cerreta di Francesco of painter condition, a craft exercised from 1849, at least, until 1888, at least, year, the last, of the last notary act in which I found it and that passed me in my hands .To remove any doubt that it could be a simple painter, in 1867 by the notary Cerrata, is indicated ornamentist and in the 85 ornamentist painter, that is, painter who connected to the architecture of the rooms the figures in guazzo that adorned the ceiling and the walls of corridors and rooms. This profession must have been shared in the family if Louis Cerreta of Joseph, by the same notary, in 1884, is referred to as a painter, while in 1886 ornamentist. Luigi found him in business until at least 1897.

In all the notary acts of the century that I consulted, Michele Cerreta turns out to be our only painter, at least until 1882 when, in one act of the notary Michele Stanco, another appears: Michele Gervasi was Angelo. To say better and much more than Michele Cerreta is the Inventory of the goods that were in the Calitri palace of the late Don Francesco Mirelli, Prince of Teora, Count of Conza and Marquis of Calitri – whose casino of Portici had been designed by the major pupil of Francesco Solimena: by Ferdinando Sanfelice, the most famous, with Domenico of the 18th century, written precisely on the occasion of the Marquis’s death. In the document dated May 26, 1857, Michele Cerreta is referred to as a portrait painter: he had gone from adorned with tempera figures for which absolute accountancy was not required, he specialized in making oil portraits of people.

In the notary protocol Michele Cerreta figures as the expert summoned to evaluate and estimate the paintings of the family of the extinct, portraits above all, some of which was his own. I wonder where that art came from. Perhaps for subsequent mediation by Giuseppe Cesta, a Calitrano who, after having learned it, may have transmitted it to someone who dragged it into the century of my ancestor. Cesta in the eighteenth century was a painter at the Immaculate. Here: Michele was Mariantonia’s father, Cerreta who married Giuseppe Nannariello, my father’s grandfather. From this Michele, who lived in the street of conception without number, we inherited the tendency to art, the nickname of family, and the house that these Nannariello, the Cerrèta, have inhabited. The house I’m still in.

The first Nannariello whose art instinct became a profession was Francesco, painter in 1899. Francis was one of Joseph’s sons, he was one of my grandfather Alfonso’s brothers. The Nannariello’s and Cerreta’s twisted. A son of Giuseppe Cerreta, Angelantonio, who was from 1864 and was a baker, was married to Vincenza Nannariello, the Garibbaldìna. I don’t know how much they have to do with me and my family. Certainly, Uncle Peppino, my father’s older brother, had a Madonna of clay. One of my father’s cousins, Angelomaria Nannariello, Rì Re Catenàzzo, had another pair of women and a St. Vincent Ferrer, also of clay.

Several of the nativity scene characters we used to do in the house had been made, some freehand, others double-matrixed, by my father. My father learned to do them from his father. Grandfather Alfonso had learned those things from his, which, in turn, he had learned from Lorenzo. Lorenzo Nannariello, my grandfather’s grandfather, however, the things he knew how to do had learned them in the family furnace, which was not, however, that of Garibbaldìna. Vincenzo, Lorenzo’s father, had married [Maria] Francesca Lampariello of Vito on June 7, 1826, who had a license for fabricar vases and another of faenzaro. Lorenzo, therefore, as a child was able to attend the family furnace, and there, like all the children who ask for clay to the baker, he must have started to make puppets, until he became capable of that art then transmitted to his. I also had an art instinct. It’s not easy for me to know where it came from.

Sometimes Mom would take me to do my homework at her father’s house to help me design, since I wasn’t really capable. When I remember those times, only one image comes back to mind: my grandfather with a nib of blue ink who, on a notebook in one of my first elementary classes, traced the shape of a bird. My grandfather looked like God and what he was doing was living. Perhaps because of the ease of those little strokes or the naturalness with which he moved his hand, I felt that I could draw myself.

Footnotes:

1. The mother forms for the carnival masks of my property lent them to the same person who ‘lost’ the terracotta Madonna mentioned. I imagine the reader sensed that even these mother forms were lost.

2. At home we had a low-relief printed in a cast a chalk door of the tabernacle with depicted the Christ risen with the cross and, all-round printed with colaggio, a half-bust in plaster of a little girl reading a book (printed on a collage). Of my own is a lion’s head in printed plaster I do not know how, which has very strong undercuts.

3. No other than Lorenzo and his son Giuseppe could have made those sculptures. I do not believe that Lorenzo’s brothers (Canio, Peter, Vitantonio and Joseph) attended the furnace, either because there were no testimonies of similar works held by their descendants, or because Lorenzo had to go there out of curiosity, out of his own personal interest, not to start working as a baker. Some Nannariello reinforced this fornacia tradition when Giuseppe Cerreta’s son Angelantonio (who just above referred to himself as his modeling father of human figures), married Vincenza Nannariello: Garibaldina.

4. Other Cerreta’s were devoted to art. Like Angelantonio (1864) or his father Giuseppe Antonio (before 1855), who were one better than the other in shaping clay figures.

Remembrance of Morris Fusco

By Richard Nannariello

Morris Fusco was a very pleasant and gentle and amiable person. He and his wife Mary Passarella Fusco had nine children over a period of nineteen years from 1920 to 1939. Mary was the dominant parent and it was clear to everyone about her matriarchal position in the family. Morris was pleasantly passive and we believe he played his passive role as a husband and father as well as he could. He was a good man!

Morris always smoked cigarettes that he rolled with a clever one hand manipulation of the paper and the other hand opening the pouch of tobacco and deftly filling the paper. When dressed up, he always wore a bow type and a dark suit and looked quite elegant and comfortable. He liked to hang around in bars and talk and drink very modestly. He had a fig tree in his side yard that he was very proud of and enjoyed the annual fruit that it produced. He had an annual ritual to dig a trench the length of the tree, partially uproot the tree, bend the tree into the hole, cover it with canvass, and then cover it with top soil. He explained that this burying it protected the tree from the harsh winter and resulted in the tree producing great figs each year. He was correct because the tree performed each year. He learned the craft in Italy.

Uncle Morris served in the army in the First World War. A monochrome photo of him in uniform hung in their home in an oval frame. If prompted, Morris would speak of the war a little and quietly revealed his pride in having participated. Every Memorial Day he would march in the White Plains parade down Main Street in his uniform and carrying a rifle on his shoulder. His body was straight and he walked proudly. His children and nephews and nieces would stand on the sidewalk and watch him. When the Second World War was completed, he shared his Veteran status with five of his sons who served some thirty years later in World War II. His sons who were Stanley (Army), Patsy (Army), Dominick (Air Force), Morris (Air Force), and Joseph (Navy). They were one of the few Five Star Families in White Plains and all returned home well and safe.

Uncle Morris was born in 1894 and died in 1981 in his ninth decade. I had the occasion to visit him in his last days of his illness in 1981 in St. Agnes Hospital in White Plains, New York. I was alone and he had no other visitors and we had a pleasant chat. He lay in bed and with his gracious smile and his memory being very active and fertile. We talked for a long while and he did most of the talking. During that conversation, he shared an ancient memories of his childhood that took place possibly about eighty years before. It was a childhood memory of picking cherries in his hometown in Italy. His storytelling was joyful and fascinating in the quality of his recollections considering the distant years. That was the last time I saw Uncle Morris and he died shortly after my visit.

The poem that follows was inspired by Uncle Morris and based on his “cherry picking” recollections of his childhood. God Love him.

Picking Cherries

He lay in the hospital room bed

Somewhere in the midst of his ninth decade

His glasses straddling

The bridge of his emaciated nose

He smiled broadly as I entered the room

All of his visitors those final days were part of the reverent final vigil

Of clichéd discussions

About how well he looks

And how soon he will be home.

At his venue in the hospital he greeted those

Who were part of the equation of his life

This dark-haired chiseled nose man

With skin the texture of suede

And the color of fine olive oil

As he gently tips toed on the cusp of eternity.

He spoke of the cherry trees

In the Italian hills

In the land of the Mezzogiorno

In the early years of the 20th century

And reminisced of his joy of picking cherries

With his friends a lifetime ago.

He recalled that spring had generously dressed

Cherry trees in silky white blooms

And in the summer abundance the cherries thrived

Populating the tree limbs

Enticing anticipating children

And he among them

To assault and plunder the summer fruit.

He explained that the cherries were tempting

And the thievery of the bronze skinned boys

Caused them to flirt

With heaven and hell

Tottering on the cusp of a venial or mortal sin

Answerable in confession to the village priest

Who was both feared and loved

Admitting their assault of the cherry tree.

As he traveled through his distant recollections

The laughter exploded from his eyes

He escaped the reality of death

With ancient reminiscing.

“Oh, those cherries were good”

And he repeated it again and then again

And with his outstretched arms

Imagined picking the cherries

With his now thin deeply veined hands.

He spoke of the local priest

Admonishing him of his venial sin

That could require multiple Hail Mary’s

As he kneeled on skinned knees

In a centuries old chapel

Where he was baptized.

He said he knew my name when I entered

But now he queried who I was

I wish I had stayed longer or returned

To share his story of the cherry trees

I wonder if the cherry trees yet peer from

The hills of his small village in Italy

Escaping the progress of the bulldozer

And the surveyor’s certain eye

Possibly still generously providing cherries

And tempting a new generation of boys

With new dreams as they maneuver their branches

Peccato! What a pity!

If those cherry trees are no longer there.

In that now slender cylinder of time

Lived a memory of a sublime moment of joy

“Oh, those cherries were good”

My God he was alive with the memory

Recalling that poignant moment of adventure

Sublime and prominent in his faded memory

The corners of his mouth

Defined a soft gentle smile

As he faced eternity

With such a joyful memory and with God’s blessing.

Grandma’s Pennies

By Richard Nannariello

Passarella Grellet Tucci (63)

White Plains, New York, Circa 1943

Grandma Filomena Farinacci Nardolillo Passarella Grellett Tucci died in 1949 and had about thirty grandchildren. This is one story by one grandchild who knew this extraordinary Lady who immigrated to the United States, had seven children, survived being a widow three times and married four times. Visits to Grandma on the third floor of the frame house on 16 Hillside Avenue, in White Plains, New York were very special in the early 1940’s.

Grandma’s pennies were the beginning

Of my concurrent youthful understanding of both

Unfettered generosity and the value of money

At the most rudimentary and highest levels

This is a warm aging memory eighty long years past

Recalling how a few Lincoln pennies defined the beginning of this revelation

My maternal Italian grandmother Filomena

Spoke little English and communicated her warmth with an engaging smile

In 1940 approaching the end of the Great Depression

And the beginning of World War Two

I was seven.

My Mother and I walked across town hand in hand

Along Main Street free of traffic lights

Passing Five and Dime stores and bakeries and a Tom McCann shoe store

And diners and drugstores and endless retail stores

Offering all the bounty the world had to offer

That both enticed and amazed the shoppers and the window watchers

Two movies houses broadcasting double features on their marquees

Peanut Joe selling popcorn and roasted peanuts from a pushcart

On the corner of Brookfield Street and Main Street

Where a chicken market offered live chickens

To be selected and slaughtered and packaged while you wait.

We exited Main Street to climb a tree lined street escalating up a hill

To Grandma’s home

A three story framed house in need of a painting

Perched on the side of a hill

That seemed to magnify its size by its perched location

There was a garden with peppers and tomatoes and parsley

Surrounded by a stringed wire fence

And in the backyard was a grape vine along a trellised wall

The grapes were fun to pick but often sour

This was not a day to visit the garden or the grape vine

But to walk the three flights of stairs to see Grandma.

Grandma lived in the attic apartment

On the third floor and greeted us at the top of the stairs

Grandma patted my head and kissed me on the forehead

Her gray hair parted down the middle

With a bun protruding from the back

On a previous visit she once had her hair

Rolling down her back and I dwelled

On the mystery of all that hair being packaged into one single bun

She was short of stature

And had no need to bend very much to embrace a seven year old

Grandma had an engaging and familiar smile

My Mother had the same smile

Grandma always put her hands in the pocket of her ubiquitous apron

And I wondered if she slept in the apron

One of the many mysteries that youth must ponder.

Grandma dispensed the most delicious

Flavored Italian biscotti treats

And provided a large glass of milk saturated with Bosco chocolate syrup

Which was stirred many times until

The texture and color were perfect

Grandma and my Mother spoke mostly in Italian

I wished that I understood their magical and incomprehensible language

And I would sometime in private moments

Speak gibberish and phony Italian

Trying to explore the rhythm and sound of it.

Grandma tinkled the coins with her hand in her apron

The sound was enticing as an evening dinner bell on a farm

She placed several Lincoln pennies in my hand

And to a child of seven in 1940

These were precious and virgin and shiny newly minted Lincoln pennies

Her generosity was magnified by the brightness of the pennies

She counted the pennies one at a time into my open hand

“Uno due tre quattro cinque”

Some came up heads and some tails

Proving some measure of the good fortune they offered

But all were shiny and appearing as bright as they day they were minted

Our two smiles embraced with unspoken joy

Both the giver and the recipient

Another pat on the head and a kiss on the forehead

My Mother and I parted down the stairs and down the hill

And my Mother stopped to light a cigarette

With a slightly guarded look

Knowing I would share her secret

A scene Grandma would never imagine or ever see

And so we proceeded downtown

Where there would be options and opportunities

To spend those priceless pennies.

Houses appeared every few blocks

With a small store front breaching the sidewalk

Where one could buy loose candy by the penny

Crooked and unwrapped Italian cigars sold by the piece

And the more expensive DiNapoli packaged cigars

Later I learned you could bet on the daily number

The stores and their penny candy were tempting

Competing with Kresge’s and Woolworth’s

For the value they provided.

I considered not being quick to spend Grandma’s shiny Lincoln pennies

That jingled so pleasantly in my pocket

Pennies that would be cautiously spent

At another time

With a more dispassionate sensibility of their value

Needing time to cherish Grandma’s pennies

Jingling them joyfully in my pocket

And holding my Mother’s hand.